Editor’s Note: The following was written on behalf of the IASLC Early Detection & Screening Committee’s Diagnostics Working Group.

In February 2022, the Diagnostics Working group of the IASLC Early Detection and Screening Committee published an article in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology that highlighted issues important for lung cancer screening during respiratory infection outbreaks.1 As the COVID-19 pandemic had a global negative impact on screening programs, the article summarized available data on possible false positive results due to respiratory infections and evaluated safety concerns for lung cancer screening during times of increased respiratory infections, especially during a regional outbreak or an epidemic or pandemic event. Further periods of increased respiratory infections are expected, so the main aim of this article was to provide guidance and stimulate research and discussions about these scenarios.

Lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) can reduce lung cancer specific mortality,2,3 but its widespread implementation is challenging even during regular times. The process includes several steps: the pre-screening phase with selection and invitations of the eligible participants, tobacco cessation counselling for active smokers, pulmonary function tests (pre and post bronchodilator spirometry and diffusion capacity), shared decision making, LDCT procedure and evaluation, team discussion, and in the case of suspicious findings, a consultation of the patient with a pulmonologist to explain the screening findings. Only some of these steps can be done remotely.

Find More at WCLC 2022

Hear more from Rudolf M. Huber, MD, PhD, during MA04 — Pulmonology, Radiology, and Staging. The session will take place from from 14:30-15:30 CEST on Sunday, August 7, in Strauss 3.

As an additional challenge, respiratory infections can lead to lesions that mimic malignant nodules and other imaging changes suggesting malignancy thus influencing scan interpretation. Three-quarters of these findings usually disappear on the 3-month follow-up LDCT examination, suggesting resolution of a prior acute infectious or inflammatory process. The increasing level of follow-up procedures or even invasive diagnostic procedures that accompany a false positive scan result introduces a higher risk to patients and adds costs to the health care system. In cases of suspicious symptoms for acute infection and inflammation, LDCT should therefore be postponed. In areas with high prevalence, tuberculosis should also be considered as differential diagnosis and must be addressed in screening programs.

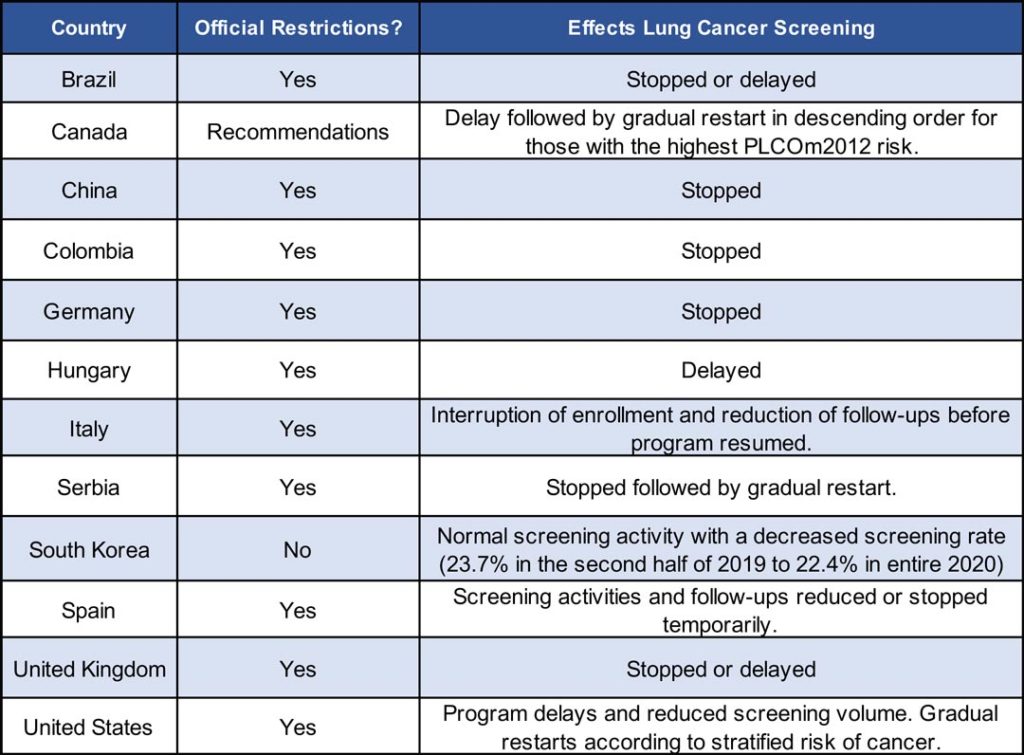

The risk of transmission of respiratory infections to the health care providers, screenees, and patients led to a temporary global stop of lung cancer and other cancer screening programs during the early months of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The situation throughout the world during the first year of the pandemic is partly summarized in Table 1.

In addition to the effects on ongoing screening programs presented in Table 1, the planned introduction of new national screening programs was further delayed in many countries. It might be speculated that the COVID-19-related delays in screening and early diagnosis of lung cancer may lead to a shift to a greater proportion of patients with advanced stage disease. While the effects of prolonged curtailing of lung cancer screening have yet to be determined, it is known that delay in diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer affects the survival of patients.4,5,6 While an only modest impact on survival may be the case if the pandemic were short-lived, a prolonged pandemic like we have been witnessing may lead to a reduction of resectable, early-stage lung cancers in the coming months and years, with a negative effect on mortality.

It is therefore crucial to find a solution to continue lung cancer screening with reduced healthcare resources considering multiple local, regional, and patient-related factors to provide optimal care. As the usual screening volume cannot be expected, mechanisms of prioritizing individuals should be discussed, especially in regions with limited resources. One option would be to prioritize individuals with the highest risk based on a quantitative lung cancer risk prediction model such as PLCOm2012 or the Liverpool Lung Project risk score7 and—if it is a repeat round—Lung-RADS category or volume doubling time. Prioritizing screening could be done by rank order of model risk estimates, starting with the highest and working down.

It is also known that various vaccinations in the upper arm can cause primarily ipsilateral axillar lymph node enlargements, which can also be FDG-PET positive.8 Therefore, it is recommended to ask lung cancer screening participants before imaging, whether they have acute respiratory symptoms or got vaccinated on the upper arm. If this is the case, it is advisable to postpone the LDCT screening or PET scan by 6 to 8 weeks to minimize unnecessary follow-up examinations.

Apart from disruption to the diagnostic pathways, treatment pathways have also been affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chemotherapy treatments of patients were mainly stopped in light of the immunosuppressive impact and potential side effects. The recent global observational Thoracic Cancers International COVID-19 Collaboration (TERAVOLT) study9 suggested that there is high mortality in patients with thoracic cancers who were infected with COVID-19.

After careful evaluation of all available data, the Early Detection and Screening Committee Diagnostics Working Group reached a consensus and recommended following safety measures for appropriate management of lung cancer screening:

- Enquire about acute respiratory symptoms by tele-medicine interviews prior to the scheduled visit and in-person before imaging procedures and ask for recent vaccinations in the upper arm. Reschedule these procedures in case of symptoms or recent vaccination for approximately 6 to 8 weeks later.

- Prior to admission of individuals into screening facilities interview individuals for recent exposures to potentially infected individuals and exposures and require infection testing (e.g. COVID-19) as is appropriate. This is to reduce likelihod of infection transmission to staff and others.

- If there is a regional high rate of respiratory infections, adapt the screening program to the actual risk level for contracting infections and switch parts of the screening program to a remote setting.

- Consider lung cancer screening after an acute infection and vaccination, where available, with a time difference of approximately 6 weeks for onsite procedures.

- If there is a back log of screening procedures prioritization of the highest risk groups using a quantitative lung cancer risk prediction model should be considered.

- Invest in educating the medical staff involved in lung cancer screening programs on the specific steps necessary to adapt the procedures according to the situation at hand.

References

- 1. Huber RM, Cavic M, Kerpel-Fronius A, et al. Lung Cancer Screening Considerations During Respiratory Infection Outbreaks, Epidemics or Pandemics: An International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Early Detection and Screening Committee Report. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(2):228-238. doi:10.1016/J.JTHO.2021.11.008

- 2. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD FR. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- 3. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503-513. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911793

- 4. Han KT, Kim W, Kim S. Does delaying time in cancer treatment affect mortality? A retrospective cohort study of Korean lung and gastric cancer patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7). doi:10.3390/IJERPH18073462/S1

- 5. Tsai CH, Kung PT, Kuo WY, Tsai WC. Effect of time interval from diagnosis to treatment for non-small cell lung cancer on survival: a national cohort study in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4). doi:10.1136/BMJOPEN-2019-034351

- 6. Byrne SC, Barrett B, Bhatia R. The impact of diagnostic imaging wait times on the prognosis of lung cancer. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66(1):53-57. doi:10.1016/J.CARJ.2014.01.003

- 7. Lebrett MB, Balata H, Evison M, et al. Analysis of lung cancer risk model (PLCO M2012 and LLP v2) performance in a community-based lung cancer screening programme. Thorax. 2020;75(8):661-668. doi:10.1136/THORAXJNL-2020-214626

- 8. Shirone N, Shinkai T, Yamane T, et al. Axillary lymph node accumulation on FDG-PET/CT after influenza vaccination. Ann Nucl Med. 2012;26(3):248-252. doi:10.1007/S12149-011-0568-X

- 9. Garassino MC, Whisenant JG, Huang LC, et al. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(7):914-922. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4.