Mariona Riudavets, MD, PhD

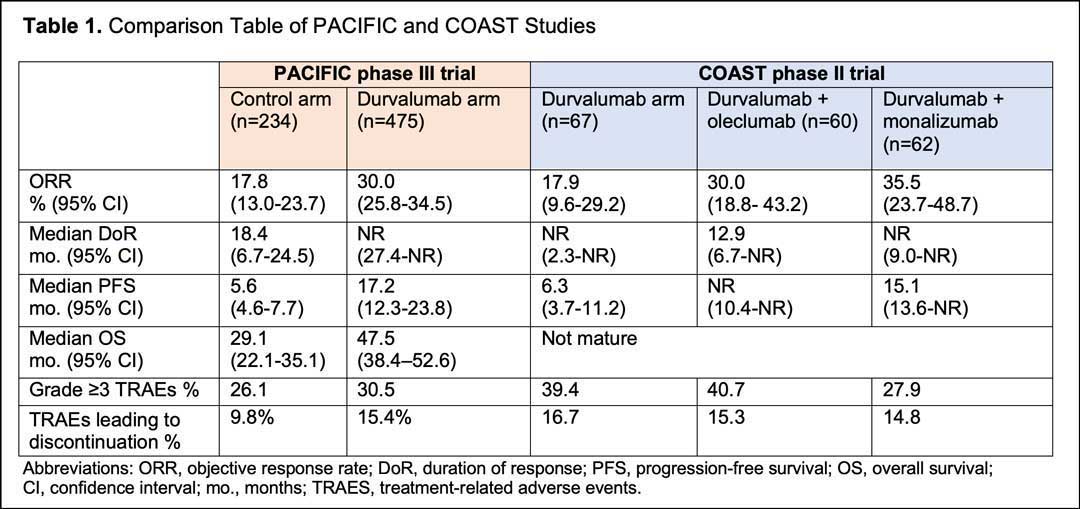

Approximately one-third of patients with NSCLC are diagnosed with unresectable, locally advanced disease.1 Results from the PACIFIC phase III trial showed a significant improvement in terms of survival for the addition of durvalumab for up to a year in following concurrent chemoradiation (cCRT), with an estimated 42.9% of patients surviving 5 years versus 33.4% for cCRT alone, and an unprecedented median overall survival (OS) of 47.5 months versus 29.1 months for cCRT alone.2,3,4,5,6 Based on these results, durvalumab has been incorporated as standard-of-care for patients with locally advanced NSCLC whose disease has not progressed after cCRT.

With the adoption of durvalumab consolidation into clinical practice, immunotherapy combination strategies are now being explored to further increase efficacy. The COAST trial is a phase II open-label study designed to investigate the efficacy and safety of new immunotherapy combinations in patients with stage III unresectable locally advanced NSCLC whose disease has not progressed following cCRT.2,3,4,5 These new strategies include the combination of durvalumab with either oleclumab or monalizumab as consolidation therapy. In COAST trial these combinations were compared to durvalumab alone.

Oleclumab is a human IgG1λ monoclonal antibody that inhibits the function of cluster of differentiation 73 (CD73).7 Upregulation of CD73 results in local immunosuppression in multiple cancer types.8,9,10 A phase 1 study of oleclumab and durvalumab showed durable responses with a manageable safety profile in patients with advanced EGFR-mutated NSCLC. Monalizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody that blocks the inhibitory receptor NKG2A from binding to the major histocompatibility complex E (HLA-E), reducing inhibition of natural killer and CD8+ T cells.11 In a phase I/II trial of patients with recurrent/metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma, monalizumab and cetuximab showed preliminary clinical activity with a manageable safety profile.12

Margarita Majem Tarruella, MD, PhD

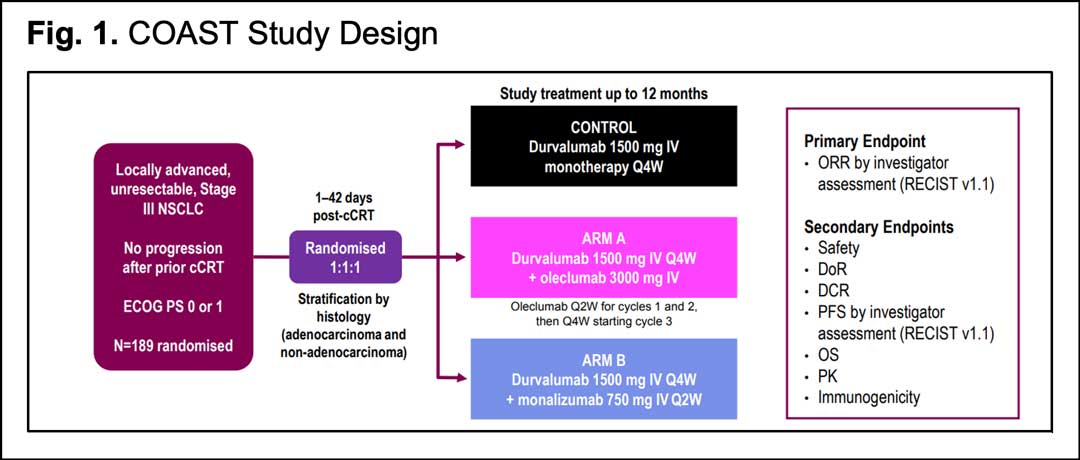

The interim analysis of the COAST trial was first presented at ESMO 2021.13 One hundred eighty nine patients with an ECOG performance status of 0-1 were randomized 1:1:1 to receive durvalumab 1500 mg either alone every 4 weeks (control arm), or in combination with oleclumab 3000 mg every 2 weeks the first 2 cycles, then every 4 weeks (arm A), or with monalizumab 750 mg every 2 weeks (arm B). Treatment was continued for up to 12 months or until patients experienced disease progression or toxicity. Stratification was made by histology.

Like the PACIFIC trial, radiotherapy had to be completed ≤ 42 days before randomization, with a minimum radiotherapy dose of 60 Grays (Gy) at 1.8 Gy/fraction or at a bioequivalent dose. The primary endpoint was objective response rate (ORR) by investigator assessment per RECIST 1.1. Secondary endpoints included safety, duration of response (DoR), disease control rate (DCR), PFS by investigator assessment, 12-month PFS rate, and OS. Archival tumor specimens were collected if available, although patients were enrolled regardless of PD-L1 status. The study design is summarized in Fig. 1.

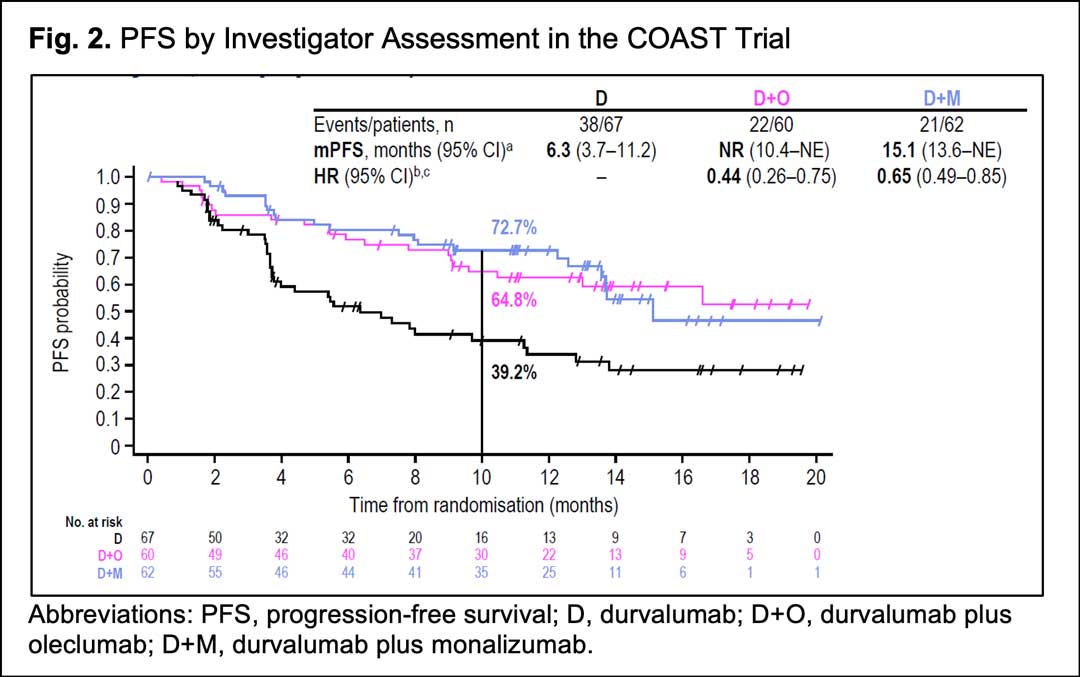

From January 2019 to July 2020, 186 patients received durvalumab alone (n=66), durvalumab and oleclumab (n=59) or durvalumab and monalizumab (n=61). Patient characteristics were consistent with those observed in the PACIFIC trial. After a median follow-up of 11.5 months (range, 0.4–23.4; all patients), both combination regimens numerically increased ORR versus durvalumab alone: ORR was 17.9% (95%CI, 9.6-29.2) with durvalumab, 30.0% (95%CI, 18.8-43.2) with durvalumab plus oleclumab and 35.5% (95%CI, 23.7-48.7) with durvalumab plus monalizumab. Of note, both combination regimens significantly improved PFS versus durvalumab alone: median PFS was 6.3 months (95%CI, 3.7–11.2) with durvalumab, not reached (95%CI, 10.4-NR) with durvalumab plus oleclumab and 15.1 months (95%CI, 13.6-NR) with durvalumab plus monalizumab (Fig 2).

The PFS benefit was observed with both combinations across various subgroups regardless of PD-L1 status, histology, ECOG performance status, or disease stage prior to cCRT. However, given the small sample sizes for these analyses, the results should be interpreted with caution.

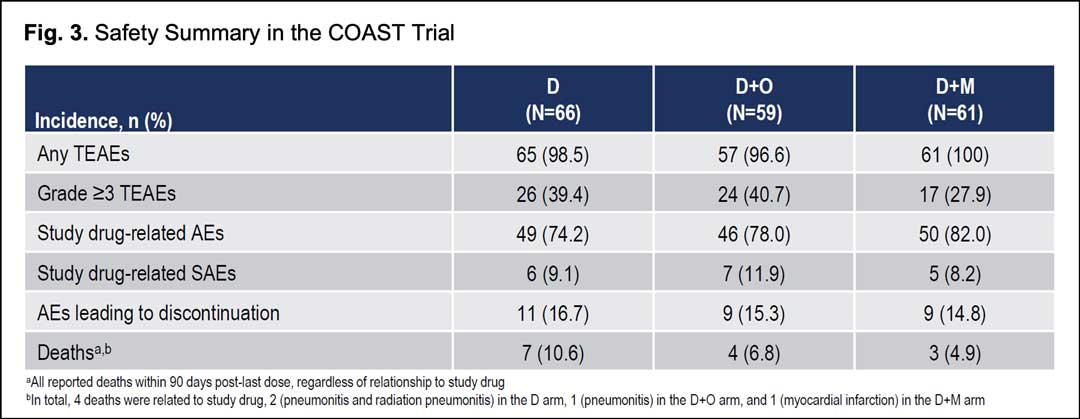

Safety profiles were consistent across treatment arms; no new safety signals were identified in either combination with similar rates of treatment-emergent adverse events and grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events for any cause. Adverse events leading to discontinuation occurred in 15.3%, 14.8%, and 16.7% of patients in the durvalumab plus oleclumab, durvalumab plus monalizumab, and durvalumab arms, respectively. There were four deaths related to study drugs: two pneumonitis and radiation pneumonitis in the durvalumab arm, one pneumonitis in the durvalumab plus oleclumab arm, and one myocardial infarction in the durvalumab plus monalizumab arm (Fig. 3).

It is important to underscore the lower ORR and PFS observed in durvalumab arm in the COAST trial in comparison with the durvalumab arm in the PACIFIC trial (Table 1). Although no direct comparisons can be done between trials, it should be noted that in the COAST trial there was a lower proportion of Asian patients, as well as a lower percentage of patients receiving prior cisplatin or randomized within 14 days of completing radiotherapy.

In conclusion, the COAST trial is the first study to demonstrate an improved efficacy and a manageable safety profile with immunotherapy combination strategies after cCRT in unresectable locally advanced stage III NSCLC irrespective of PD-L1 status. These data support further evaluation of these combinations in a registration-intent study. To this end, the PACIFIC-9 trial (NCT05221840) is a phase III, prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter international study assessing the efficacy and safety of durvalumab in combination with either or monalizumab in patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC whose disease has not progressed following platinum-based cCRT.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chansky K, Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: External Validation of the Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2017;12(7):1109-1121. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2017.04.011

- 2. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919-1929. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1709937

- 3. Antonia SJ, Özgüroğlu M. Durvalumab in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):869-870. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1716426

- 4. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Overall Survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(24):2342-2350. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1809697

- 5. Faivre-Finn C, Vicente D, Kurata T, et al. Four-Year Survival With Durvalumab After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC—an Update From the PACIFIC Trial. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. Published online January 2021:S1556086421000228. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2020.12.015

- 6. Spigel DR, Faivre-Finn C, Gray JE, et al. Five-Year Survival Outcomes From the PACIFIC Trial: Durvalumab After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO. Published online February 2, 2022:JCO.21.01308. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01308

- 7. Geoghegan JC, Diedrich G, Lu X, et al. Inhibition of CD73 AMP hydrolysis by a therapeutic antibody with a dual, non-competitive mechanism of action. mAbs. 2016;8(3):454-467. doi:10.1080/19420862.2016.1143182

- 8. Hay CM, Sult E, Huang Q, et al. Targeting CD73 in the tumor microenvironment with MEDI9447. OncoImmunology. 2016;5(8):e1208875. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2016.1208875

- 9. Inoue Y, Yoshimura K, Kurabe N, et al. Prognostic impact of CD73 and A2A adenosine receptor expression in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(5):8738-8751. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.14434

- 10.Vijayan D, Young A, Teng MWL, Smyth MJ. Targeting immunosuppressive adenosine in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(12):709-724. doi:10.1038/nrc.2017.86

- 11. André P, Denis C, Soulas C, et al. Anti-NKG2A mAb Is a Checkpoint Inhibitor that Promotes Anti-tumor Immunity by Unleashing Both T and NK Cells. Cell. 2018;175(7):1731-1743.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.014

- 12. Cohen RB, Bauman JR, Salas S, et al. Combination of monalizumab and cetuximab in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer patients previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and PD-(L)1 inhibitors. JCO. 2020;38(15_suppl):6516-6516. doi:10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.6516

- 13. Martinez-Marti A. LBA42 – COAST: An open-label, randomised, phase II platform study of durvalumab alone or in combination with novel agents in patients with locally advanced, unresectable, stage III NSCLC. Annals of Oncology (2021) 32 (suppl_5): S1283-S1346. 10.1016/annonc/annonc741