Appropriate and swift diagnosis and treatment are crucial for patients with lung cancer but can be elusive for many due to cost, healthcare disparities, and other barriers.

Factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity can affect not only access to screening and care but also disease outcomes, as can the economic resources and quality of the healthcare system in a patient’s country or region. Moreover, to serve them well, doctors must study the issues important to patients and help them strike a balance between the promise of innovative new technologies and their financial and physical costs.

In an education session on value (ES05), five experts discussed value-based analyses, methods for overcoming barriers to care, and concepts for health system reform that could help doctors meet the needs of patients with lung cancer throughout their journeys from screening to treatment.

Improving Care in Lower-Income Countries

An access-related conundrum that requires immediate attention from the international health community is that lung cancer incidence and mortality rates are the highest in the countries least able to address them, said Ricardo Sales do Santos, MD, PhD, of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein and Hospital Cárdio Pulmonar da Bahia in Brazil.

As a result, he said, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) need help establishing lung cancer screening and treatment programs.

This is particularly true because the countries dubbed LMICs by the World Bank—including Brazil, China, Argentina and those in Africa—are home to more than 80% of the world’s 1.3 billion smokers, who will likely account for over 70% of all global smoking-related deaths. “We expect more than 2 million related deaths [from lung cancer in LMICs] by 2040, contrasting with 850,000 in high-income countries” such as the United States, Canada, Greenland, Australia, Saudi Arabia and much of the European Union, said Dr. Santos, who is a member of the IASLC Lung Cancer News Editorial Group and of the Latin America Group and Screening & Early Detection Committee.

Furthermore, spotty health systems in some LMICs leave care and access particularly lacking in certain regions, where patients may face obstacles including language barriers, unemployment, health illiteracy, low education levels, geographic isolation, an inability to pay for medication, a lack of transportation, and long waiting times.

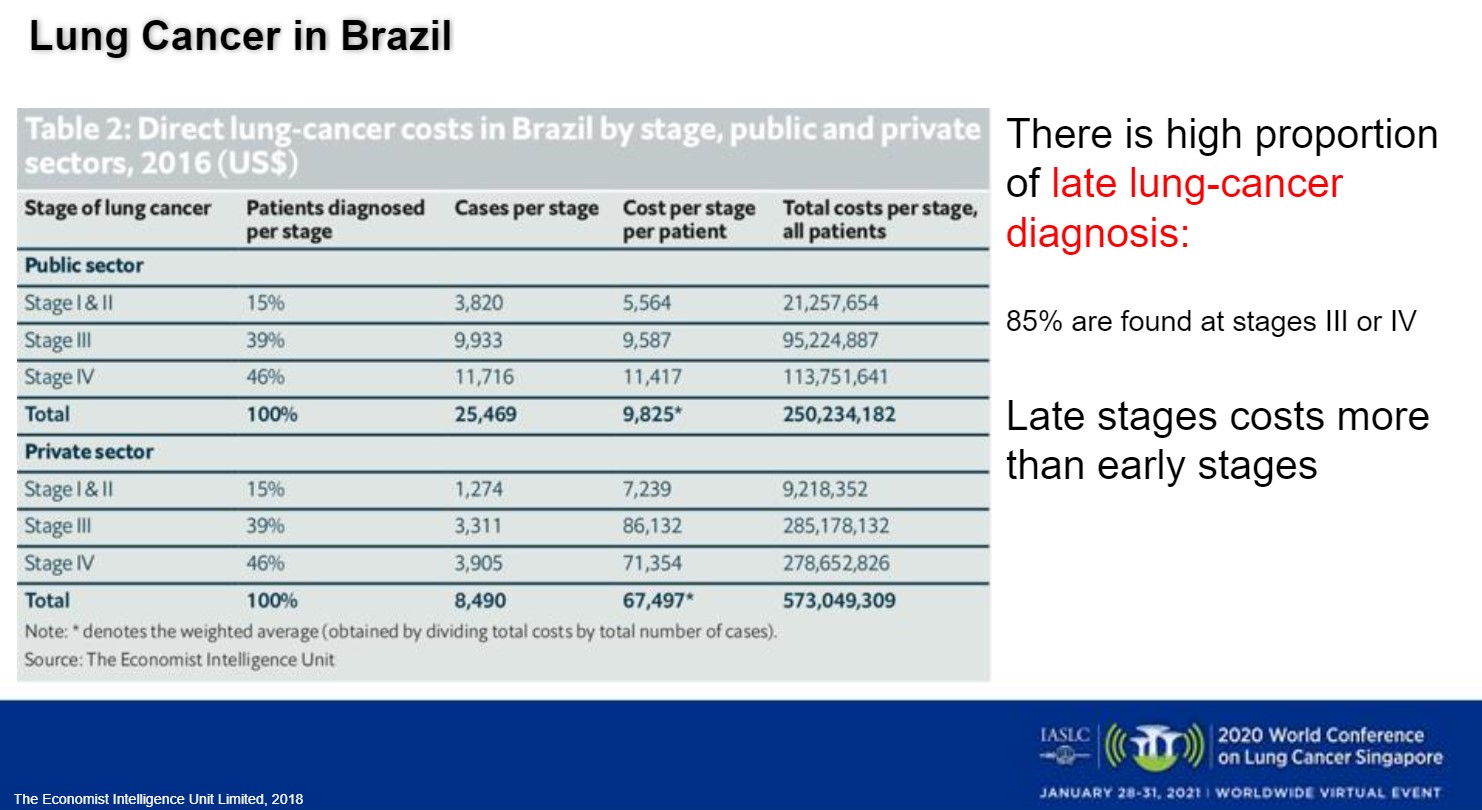

Although prevention is improving in many of these countries, early diagnosis needs bolstering through screening and expanded medical infrastructure. More than 85% of Brazil’s patients with lung cancer are diagnosed with late-stage disease, which is “2 to 10 times more expensive to treat than early-stage in terms of money—but, of course, the cost is also the cost of lives,” Dr. Santos said (Fig 1).

To build resources in his country, Dr. Santos is collaborating to seek funding for mobile screening units and was the lead investigator in the Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial, which imaged 790 eligible patients using low-dose CT. As part of an ongoing study there, five institutions have screened 3,277 patients in the states of São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, and Bahia, he added.

Dr. Santos also supports stabilizing health programs by mixing public and private elements, improving public education about lung cancer and screenings, and providing more specialists in countries such as India, which has 1 oncologist for every 16,000 patients, compared with a ratio of 1:100 in the United States.

Additional challenges will involve improving the quality of lung cancer care through wider access to specialized medicine, multidisciplinary teams, lung and radiology centers, robotic surgery, and data integration, Dr. Santos said.

Increasing Access to Novel Agents

Among the challenges to lung cancer care in LMICs—and in resource-constrained regions of high-income countries—is a restricted ability to use targeted drugs and immunotherapies due to a lack of cost-effectiveness in those settings, said Gilberto Lopes, MD, of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Health System. Dr. Lopes is chair-elect of the IASLC Ethics Committee and a member of the Brazil Strategy Working Group.

“We have, without a doubt, made a huge difference for patients with lung cancer in those countries where we can actually have access to these new technologies,” he said. “But, unfortunately, for those of us who practice in lower-income countries, we need to find many more innovative ways to try to increase access, because at current prices, it is clear that many of our new technologies are not cost-effective in lower-resource settings.”

Dr. Lopes pointed out that, over the years, novel treatments have steadily improved the outcomes of patients with NSCLC, boosting their prognosis from a low of 4 to 6 months with best supportive care to a high of 2 years or more for those with mutations targetable by tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

As an example, he noted that the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab has increased 5-year survival in previously treated, metastatic NSCLC from 5% to between 12% and 25%. In addition, the novel TKI osimertinib has improved progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and toxicity in previously untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC compared with standard EGFR TKIs. “We would think that, because of that, [osimertinib] should be a shoo-in [for use worldwide], but that is only if we do not consider the issues of price and cost, and therefore access,” Dr. Lopes said.

He highlighted the drug affordability gap by pointing out that, even as the costs of drug development rise, per-patient investments in cancer control total just $0.54 in India, $4.32 in China, and $7.92 in South America, compared with $183 in the United Kingdom, $244 in Japan, and $460 in the United States. Furthermore, he said, government drug authorities take longer to approve new treatments in lower-income countries than in higher-income ones, sometimes by a margin of years.

As a result, testing for driver mutations occurs much less frequently in lower-income countries than in richer ones, as does treating patients with novel agents.

That issue contributes meaningfully to the gap in cost-effectiveness, since studies have shown that testing for biomarkers and treating accordingly makes cancer care more cost-effective, Dr. Lopes said. In fact, he said, using biomarkers when developing treatments for lung cancer increases trial success rates from 11% to 60% and decreases development costs by 27%.

Still, he said, without resolving the problem of high drug costs, simply relying on the use of biomarkers and existing generics and biosimilars will not close the gulf in affordability. To establish more accessible drug pricing, one tactic could involve compulsory licensing, under which an LMIC’s government, in the public’s interest, can compel the generation of a generic drug before the patent has expired on the agent it mimics. Dr. Lopes also suggested establishing adequate healthcare funding in LMICs through universal coverage, value-based insurance design and a global fund to fight cancer.

Critically Evaluating Trial Results

The bottom line is that getting effective and affordable lung cancer screening and treatment to patients everywhere will depend on one basic tenet: common sense, argued Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, a medical oncology fellow and an assistant professor of Public Health Sciences at Queen’s University in Canada.

He said that this “common sense revolution” should be waged on three fronts: teaching trainees to critically appraise the literature while focusing on the main patient concerns of longer and better life; conducting cancer research relevant to those patient needs; and setting new policies.

The reason doctors must be willing and able to critically evaluate the results of studies is that “there are so many issues that can distort the results of a clinical trial,” Dr. Gyawali said.

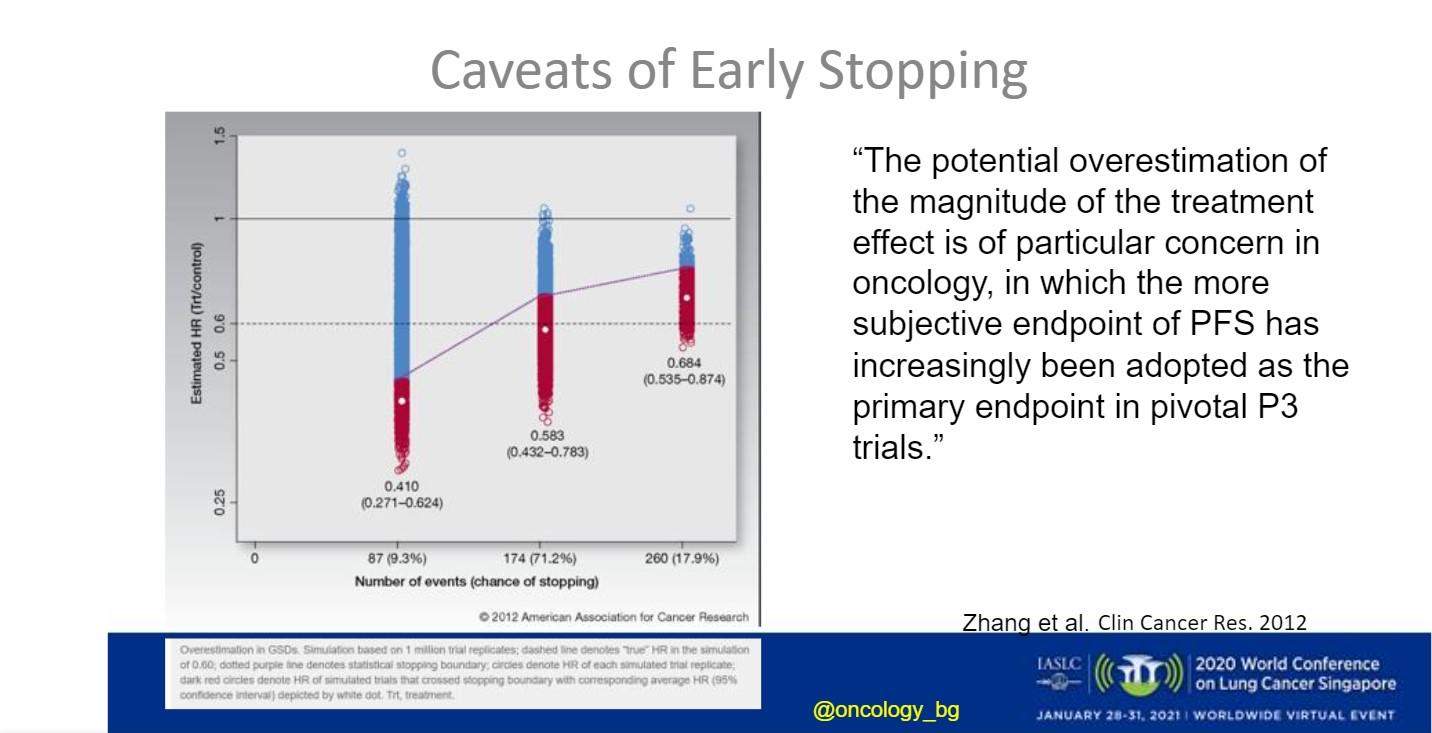

For instance, he said, in the ADAURA trial of osimertinib versus placebo in patients with early, EGFR-mutated NSCLC who had undergone complete surgical resection, there were questions about whether patients had received proper chemotherapy and staging of brain metastases, as well as uncertainty about whether it was reasonable to use disease-free survival as a surrogate endpoint for OS. He added that the early stopping of a trial due to good results can cast findings into question, because “the earlier the trial is stopped, the greater is the potential for overestimation of clinical benefit,” (Fig 2).

Also potentially misleading is the fact that, when trial populations are very large, “any difference will turn out to be statistically significant,” Dr. Gyawali said. As an example, he cited the nearly 1,100-patient SQUIRE trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without necitumumab, which demonstrated a statistically significant OS of 1.4 months.

“The cost of [necitumumab] is quite high, which does not justify this small improvement in survival,” said Dr. Gyawali, noting that, as a result, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network removed the three-drug regimen from its clinical treatment guidelines for patients with metastatic squamous cell lung cancer. “There are many necitumumabs out there in oncology that need to be evaluated in a similar way,” he said.

Trial results can also be confounded when the P values for subgroups are not corrected for multiple comparisons, Dr. Gyawali said, adding that, “in a randomized controlled trial, if we do not use the ideal [treatment as a] competitor, then we can show any drug as being useful.”

Dr. Gyawali agreed with the need for more homogeneous delivery of lung cancer care, suggesting the launching of a “cancer groundshot” that encourages and funds initiatives “to implement the interventions that we already know to work equally throughout the world,” such as surgery and radiotherapy.

He added that public and academic funding have provided the majority of support for trials that led to increased survival in patients with lung cancer, and that this trend should continue.

“We need more and more publicly funded, academia-sponsored trials to answer the questions that actually matter to the patients,” he concluded.

Considering Histology and Socioeconomic Factors

Even in countries and regions where appropriate treatment for lung cancer is available, patients can face disparities in obtaining care, often due to individual disease characteristics and socioeconomic issues, said Linda Coate, MD, a medical oncologist with the University Hospital Limerick, Ireland, and chair-elect of the IASLC Communications Committee.

Beyond the fact that lung cancer is composed of numerous histologic subtypes, issues including age, gender and ethnicity contribute to differences in the way the disease is treated and how it responds. Those concerns, Dr. Coate said, shine a light on the need for health equity, which she defined as “everyone having a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible.”

While lung cancer is a disease of the elderly, multiple studies have shown that “age alone is not a reason to withhold or moderate treatment,” Dr. Coate said. Nevertheless, some doctors hesitate to use aggressive treatments such as platinum-based chemotherapy in an older population.

“A comprehensive geriatric assessment should probably be used to investigate frailty, but this has not been widely adopted,” she said.

There are also inconsistencies regarding gender, Dr. Coate said, pointing out that women face a greater risk of developing lung cancer than men, possibly because their cancers have less effective DNA-repair mechanisms. Yet, across all datasets, women tend to respond better to lung cancer treatment, perhaps due to the influence of hormones. As a result, “it is probably likely that men and women should have different types of treatment,” Dr. Coate said, “but, at present, this is not the case.”

Another complicating factor, she said, is the “extraordinary gap between mortality (rates) from lung cancer for different races.” CDC data show that, in 2016, black and white populations had lung cancer death rates of 41.2 and 41.5 per 100,000 people, respectively, compared with a rate of 16.6 per 100,000 for Hispanics. Citing National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) data, Dr. Coate added that lung cancer develops disproportionately in blacks compared with whites, with “black patients with lung cancer…likely to die sooner than white patients.”

But more investigation is needed, Dr. Coate cautioned, as the NLST, whose population was 90.8% white, generated “a paucity of data regarding outcomes for other races.”

She added that age, gender, and ethnicity are not the most important of the many factors that shape lung cancer incidence rates and outcomes.

Other contributors, she said, include demographics, epidemiology, politics, economics, sociocultural concerns, technology, physical disability, comorbidities, citizen expectations, innovation, and opportunity. For instance, she noted, the lung cancer mortality rate in men is several times higher in the least educated versus the most educated.

“Socioeconomic factors are the strong drivers of disparity, (and) equity of access to quality care is crucial,” Dr. Coate said. “More research is needed in this area, as well as population-based political action to drive change.”

Applying Value Analyses in Radiotherapy

The concept of weighing value in lung cancer care is key across every specialty on the multidisciplinary team, and that includes radiotherapy, said Fumiko Chino, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Looking at lung cancer treatment as a whole, including surgery, chemotherapy/immunotherapy, and hospitalization, she noted that radiation costs comprise a minority of the price tag, “and this can be associated with the potential for high-value care.”

But how should value be defined within this setting? Various stakeholders may have different opinions, Dr. Chino said.

Analyses of cost-effectiveness have been conducted on many of the advances of the past two decades, including intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) as an alternative to 3D conformal radiation; proton beam and carbon ion radiation; image-guided radiation therapy; respiratory gating and breath-hold radiation therapy; and MR-linac, which can “allow quite elegant sparing of normal tissues,” Dr. Chino said. While some of these therapies may have a high startup cost for the clinics that offer them, a strategy such as SBRT may actually have the lowest out-of-pocket costs for patients and take the shortest amount of time to administer, she noted.

Monetary costs do not encompass the whole equation, as treatment modalities with much higher costs may provide benefit in the long-term by decreasing late events that can be both morbid and financially costly. For example, one study showed that patients who received proton beam therapy rather than IMRT may benefit from greater protection against late heart damage, due to smaller radiation doses.

To truly understand the value of a treatment, Dr. Chino said, it’s crucial to carefully evaluate the findings of studies assessing cost-effectiveness.

She mentioned two studies in patients with stage I NSCLC, one of which found that SBRT was not cost-effective versus lobectomy for operable patients while the other determined that it was, with the variability coming from the assumptions that each study used. In another example, while a study found that thoracic radiation therapy was cost-effective at 24 months in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, Dr. Chino noted that the result may be meaningless to patients who do not live that long.

“All of the mixes that go into cost-effective analysis, in terms of what studies they use for their outcomes analysis and what potential complications they (factor in), can really change the analysis,” she said.

The educational discussion concluded with a live Q&A session.