The opportunity to overcome the century-long global pandemic of lung cancer—the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide—has never been greater. Indeed, the list of positive developments in recent years continues to grow. Not only can those in the field of thoracic oncology point to increased prevention measures through tough tobacco control policies and the advent of early detection through screening at-risk populations as keys to reducing the burden of lung cancer, we also have access to guideline-concordant management of incidentally detected lung nodules. In addition, rapid advances in our understanding of cancer biology are delineating lung cancer into biomarker-indentified subsets that can be specifically targeted with more effective treatments.

The multiplicity of advances, exciting as they are, present a daunting implementation challenge. How do we optimally execute evidence-based care to bring the benefits of discovery to all without delay?

Of all the exciting developments in lung cancer care, the possibility of early detection must rank near the top of the most important. The goal of early detection, of course, is to increase the proportion of patients for whom curative-intent treatment is possible and thereby reduce lung cancer mortality. Achieving this population-level benefit also mandates that surgical resection must be optimally performed, so the promised cure can be delivered. Most long-term survivors of lung cancer are part of the minority of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients who undergo curative-intent surgery. In the US, this is approximately 25% to 30% of all NSCLC patients; the proportion is significantly lower in most other countries.

This begs the question: Do we routinely derive the full benefit of curative-intent surgical resection?

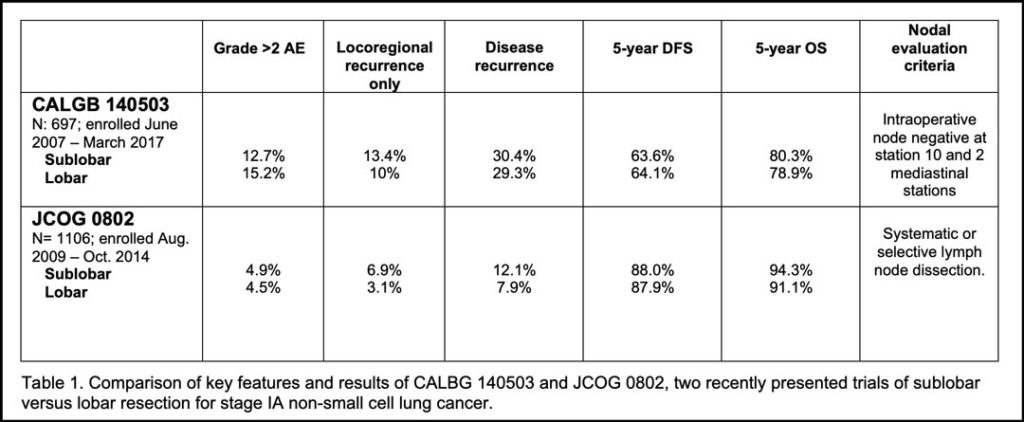

The aggregate survival of patients fortunate to be able to undergo curative-intent lung cancer surgery, is, to phrase it delicately, a goal we have yet to fully realize. The size of this opportunity is illustrated in a “tale of two trials” and analysis of enrollees into a third. Two recent practice-changing trials—CALGB 140503 (Alliance), conducted in North America, and JCOG0802, conducted in Japan, compared sublobar resection to lobectomy for patients with small (≤2cm) peripheral NSCLC (stage IA1 and IA2, in the 8th edition TNM staging system).

It was the best of times. These two trials arrived at the same conclusion: In highly selected patients, sublobar resection provides similar or superior survival compared to lobar resection.

It was the worst of times. These trials also revealed a striking disparity in outcomes: In a cross-trial comparison, curative-intent lung cancer surgery in North America, even for the earliest of lung cancer stages, seemed more hazardous and fraught with greater risk for failure than similar surgery in Japan (See Table 1).1,2

Why? The answer might be gleaned from an unplanned analysis of enrollees in a third, ongoing study, the Adjuvant Lung Cancer Enrichment Marker Identification and Sequencing Trial (ALCHEMIST) Alliance A151216.3

Patients with completely resected pathologic stage IB to IIIA NSCLC were enrolled into ALCHEMIST for biomarker screening as a preliminary step towards possible subsequent enrollment into any of several available biomarker-directed adjuvant therapy trials.

Kehl et al evaluated the rates of guideline-concordant surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy use among 2,833 patients enrolled into ALCHEMIST from August 18, 2014, to April 1, 2019, who were not subsequently enrolled into a biomarker-directed adjuvant therapy trial. The objectives of this unplanned analysis were to evaluate the quality of surgery and the patterns of adjuvant therapy use.

For the quality of surgery, the questions asked:

- Did patients undergo an anatomical surgical resection?

- Did patients undergo adequate lymph node evaluation, defined as examination of at least one hilar/intrapulmonary lymph node and lymph nodes from at least three mediastinal stations?

For the quality of adjuvant therapy, the questions asked:

- Did patients receive any adjuvant chemotherapy?

- Did patients receive 4 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy?

- Did patients receive any cisplatin-based chemotherapy?

The analysis found 95% of patients underwent an anatomical surgical resection; however, only 53% had adequate lymph node dissection; 57% received some adjuvant chemotherapy; 44% received at least 4 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy, and 34% received cisplatin-based adjuvant therapy.3

Nothing about these results is either reassuring, or, sadly, even in a US clinical trial population, surprising. The pathologic nodal staging quality gap is a worldwide phenomenon, its prevalence and adverse effects have been described in multiple datasets, but the possibility of its correction is also now being addressed. Heightened awareness of this quality problem has led to several efforts to overcome it.

The IASLC has re-defined the completeness of lung cancer resection beyond the absence of disease at the surgical resection margin, to include information about the likelihood of residual nodal disease by creating the ‘R-uncertain’ category, which predominantly includes populations with sub-optimal nodal evaluation (including 47% of the analyzed ALCHEMIST cohort).4 Such patients have been shown in multiple datasets to have significantly inferior survival.5

The American College of Surgeons is now promoting Operative Standard 5.8, which requires the combination of negative resection margins, examination of at least one hilar or intrapulmonary lymph node station and at least three mediastinal lymph node stations in >70% of lung cancer resections in 2021 and in >80% of resections performed from 2022 onwards at Commission on Cancer-accredited programs.6 The benefit of compliance has already been corroborated in an analysis of the US Veterans Affairs population.7

Under-utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy—another finding in this population sufficiently fit for enrollment in a clinical trial exploring novel adjuvant therapies—demonstrates additional opportunity to improve the long-term outcomes of surgical resection. Although the benefits of adjuvant platinum-doublet chemotherapy are modest, with only an absolute 5% overall survival improvement at 5 years, this benefit has been established for almost two decades.8 Unfortunately, it is likely that the findings in an unselected population not enrolled in a clinical trial—the vast majority of lung cancer patients—will be worse than what Kehl et al have described.

What does this all mean? There needs to be greater effort to highlight the pathologic nodal staging quality gap. The differences in outcomes between surgery performed on a Japanese population by Japan-trained surgeons, and a North American population by predominantly US-trained surgeons may have many different explanations. Conceptually, these explanations range from biologic differences in the aggressiveness of cancer or the adroitness of the host immune response between the North American and Japanese populations, to a red herring, a spurious finding in a purely descriptive, non-comparative report.

Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that JCOG0802 was performed at the best of the best Japanese institutions by academic surgeons, while CALBG 140503 more closely represented the spectrum of institutions and surgeons, including a high proportion of surgeons working in the US, including a high proportion of surgeons working in US, including a high proportion of surgeons working in community healthcare systems (where 85% of US lung cancer surgery is performed). It is also interesting that the stringency of the intraoperative preliminary pathologic nodal staging required for eligibility differed between trials: CALGB 140503 only required frozen section proof of non-involvement of the hilar and two mediastinal nodal stations, whereas JCOG0802 required systematic or lobe-specific nodal dissection. Put another way, the minimum intraoperative eligibility requirement of CALGB 140503 permitted R-uncertain resections, whereas all patients enrolled into JCOG0802 were required to have met IASLC R0 resection criteria.

With the 9th edition of the TNM, the R-Factor Subcommittee will probably emphasize the need to raise the overall quality of lung cancer surgery to increase the proportion of patients whose surgery attains the more stringent definition of R0 (negative margins, systematic nodal dissection or lobe-specific nodal dissection, uninvolved highest mediastinal nodal station).11

The effort of the American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer to bring about higher quality surgical practice in the US, onerous as it may seem to some, is a step in the right direction. The emergence of more effective biomarker-directed adjuvant therapies should raise enthusiasm for optimal adjuvant therapy, but that comes with the challenge of ensuring biomarker testing for all. There also remains the huge challenge of understanding the true stage-independent risk of residual disease in patients who have undergone curative-intent surgery (that 30% of the CALGB 140403 population who, despite ‘complete resection’ of stage IA NSCLC, nevertheless suffered disease recurrence). We also need to be able to identify patients whose cancer is truly cured by surgery alone; arguably, this includes most long-term survivors currently treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, given the 5% absolute survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy.8

Only by continuing to enroll patients into clinical trials designed to ask these important questions will we be able to answer them. Only by answering these questions will we ever be able to realize the full promise of the exciting advances in our understanding of cancer biology. Ideally, the “best treatment” for our patients is a clinical trial, because clinical trials give us access to tomorrow’s treatment today.

References

- 1. Altorki NK, Wang X, Kozono D, et al. Lobar or Sub-lobar Resection for Peripheral Clinical Stage IA = 2 cm Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Results From an International Randomized Phase III Trial (CALGB 140503 [Alliance]). J Thorac Oncol. 2022 Sept;17(9)Suppl:S1-S2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2022.07.012

- 2. Saji H, Okada M, Tsuboi M, et al; West Japan Oncology Group and Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2022 Apr 23;399(10335):1607-1617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02333-3. PMID: 35461558.

- 3. Kehl KL, Zahrieh D, Yang P, et al. Rates of Guideline-Concordant Surgery and Adjuvant Chemotherapy Among Patients With Early-Stage Lung Cancer in the US ALCHEMIST Study (Alliance A151216). JAMA Oncol. 2022 May 1;8(5):717-728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.0039. PMID: 35297944; PMCID: PMC8931674.

- 4. Rami-Porta R, Wittekind C, Goldstraw P; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Staging Committee. Complete resection in lung cancer surgery: proposed definition. Lung Cancer. 2005 Jul;49(1):25-33. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.01.001. PMID: 15949587.

- 5. Rami-Porta R, Wittekind C, Goldstraw P. Complete Resection in Lung Cancer Surgery: From Definition to Validation and Beyond. J Thorac Oncol. 2020 Dec;15(12):1815-1818. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.09.006. Epub 2020 Oct 13. PMID: 33067147.

- 6. Available at: CoC Standard 5.8: Requirements & Best Practices – YouTube; accessed on October 29, 2022.

- 7. Heiden BT, Eaton DB Jr, Chang SH, et al. Assessment of Updated Commission on Cancer Guidelines for Intraoperative Lymph Node Sampling in Early Stage NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2022 Aug 30:S1556-0864(22)01551-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.08.009. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36049657.

- 8.Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, et al; LACE Collaborative Group. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jul 20;26(21):3552-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030. Epub 2008 May 27. PMID: 18506026.

- 9. Wu YL, Tsuboi M, He J, et al; ADAURA Investigators. Osimertinib in Resected EGFR-Mutated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 29;383(18):1711-1723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027071. Epub 2020 Sep 19. PMID: 32955177.

- 10. Felip E, Altorki N, Zhou C, et al; IMpower010 Investigators. Adjuvant atezolizumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): a randomized, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021 Oct 9;398(10308):1344-1357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02098-5. Epub 2021 Sep 20. Erratum in: Lancet. 2021 Sep 23. PMID: 34555333.

- 11. Edwards JG, Chansky K, Van Schil P, et al; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee, Advisory Board Members, and Participating Institutions. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Analysis of Resection Margin Status and Proposals for Residual Tumor Descriptors for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020 Mar;15(3):344-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.10.019. Epub 2019 Nov 13. PMID: 31731014.