The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes the value of liquid biopsy in managing patients with cancer, and the agency is actively working to bring these assays to the clinic. Harpreet Singh, MD, Director of the Division of Oncology 2, shed light on past FDA efforts related to approval of liquid biopsy technologies as well as those currently underway.

“Liquid biopsies for cancer require close interaction between the oncologist regulating cancer drugs and physicians and scientists who regulate devices,” Dr. Singh explained. Because of this, regulatory oversight of liquid biopsies falls under the purview of the Oncology Center of Excellence, which oversees the review of oncology products across three centers. These include: the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, which reviews targeted therapies and immunotherapy drugs; the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, the center that oversees the regulation of gene and cell therapies; and the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, the center that oversees companion and complimentary diagnostics as well as therapeutic devices.

The FDA has approved three liquid biopsy technologies since 2016, and several others have been granted breakthrough designation status. The first two assays approved—the Epi proColon test, designed to screen for colon cancer, and the cobas EGFR Mutation Test, developed as a companion diagnostic to erlotinib and later to gefitinib—rely on real-time PCR. In August 2020, the Guardant 360 assay became the first approved liquid biopsy next-generation sequencing (NGS) companion diagnostic test, in this case for identifying biomarkers that predict for benefit with osimertinib.

To bring more liquid biopsy technologies to market, as well as new therapies, the FDA is looking closely at two key areas where analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from a liquid biopsy sample can influence treatment selection: the adjuvant setting and the metastatic setting.

“There is a need for innovation in terms of adjuvant drug development given the extended time to drug approval, the large size of trials required, and overtreatment of the majority of patients,” Dr. Singh explained. “The detection of ctDNA after surgery may be an indication of molecular disease progression that precedes clinical relapse.”

Steps Toward Standardizing Approaches, Communicating Broadly

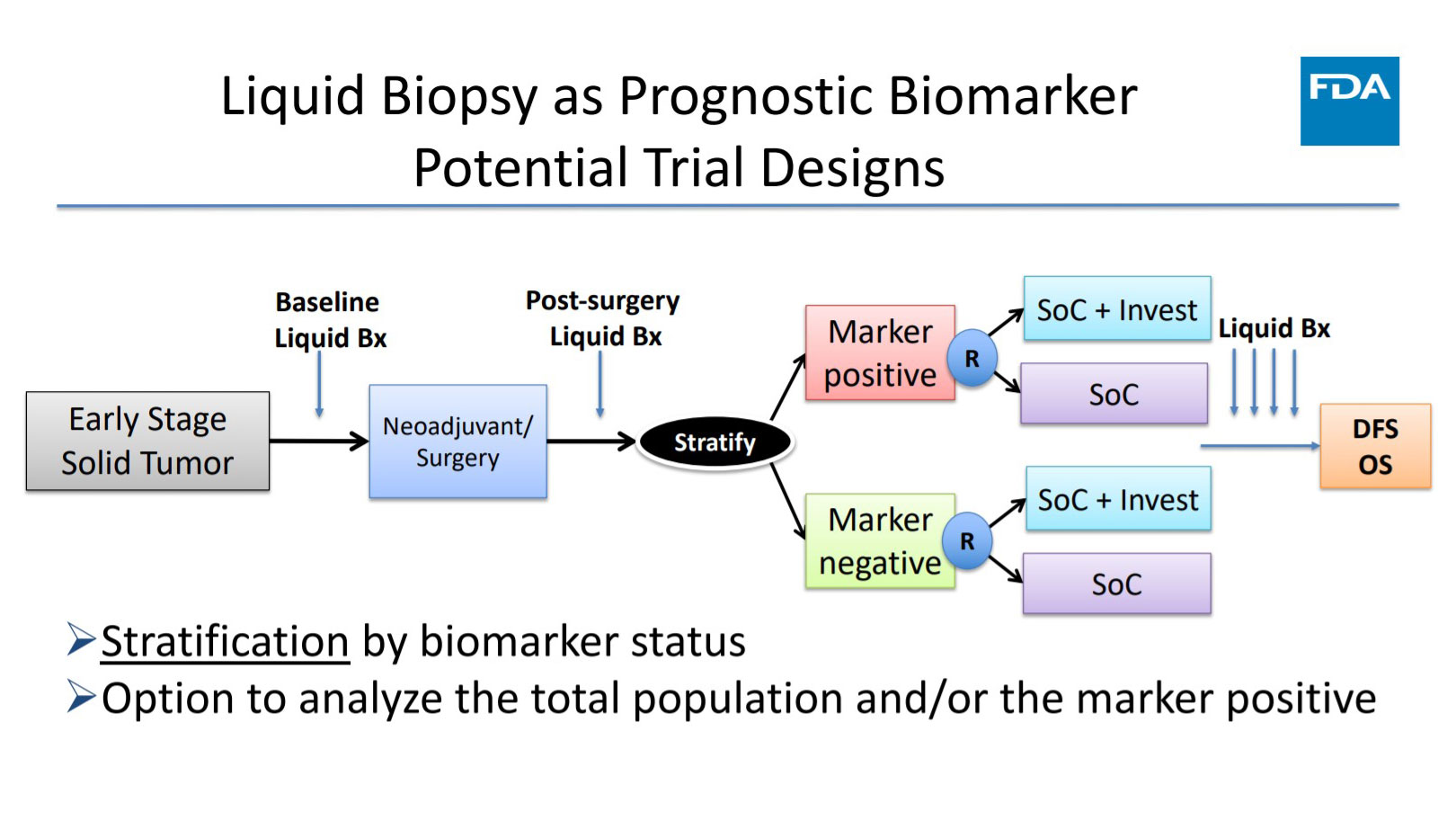

Dr. Singh then went on to describe various scenarios in which ctDNA could be incorporated into the design of prospective adjuvant therapy trials. She stressed that for any adjuvant trial to establish ctDNA as a biomarker of response, it needs to demonstrate a correlation between change or clearance of ctDNA with drug activity. The same holds true for survival. “In order for ctDNA to be validated as a surrogate for overall survival, the strongest evidence would need to come from prospective randomized clinical trials or meta-analysis of similarly conducted trials that demonstrate that ctDNA is predictive of treatment effects and long-term outcomes,” Dr. Singh said.

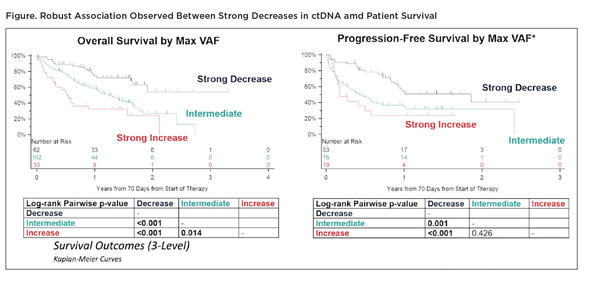

With regard to use of ctDNA in the metastatic setting, the Friends of Cancer Research initiated the ctDNA for Monitoring Treatment Response (ctMoniTR) project that aims to bring together pharmaceutical companies, diagnostic labs, academic researchers, patient advocates, and government health officials, including the Oncology Center of Excellence, to validate use of blood-based biomarkers for determining treatment efficacy. Step 1 of the project, now completed, involved aligning all stakeholders on the methodology to analyze combined ctDNA data from past clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced NSCLC, with the aim of determining whether promising trends observed in smaller data sets could be replicated in a larger dataset. “The hope was that this collaborative effort would bring together a larger and more robust combined dataset than if any one stakeholder attempted to compile these data on their own,” said Dr. Singh.

Harmonizing the data was no easy feat given inconsistencies in the timing of ctDNA assays and tumor response evaluations across the pooled dataset. Nevertheless, the researchers observed clear associations between the change in ctDNA levels following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and treatment outcomes (Figure).

“This project provided a substantial advance in our knowledge from the retrospective data used in Step 1,” said Dr. Singh. It also helped the group to identify the limitations of this type of collaborative data analysis, enabling them to better plan for the next phase of the project. Step 2 of the ctMoniTR project is now underway, with the aim of determining feasibility in other cancer types and generating results in a shorter timeframe to accelerate knowledge about the role of liquid biopsies in cancer research and care.

Looking even more broadly, the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence launched Project Orbis in 2019, an initiative in which the submission packages for oncology products can be concurrently reviewed by international regulatory agencies to speed access to these products worldwide. “The FDA truly views oncology drug development as a global endeavor…. It is our hope that as the field of liquid biopsies advances, these technologies can also be part of our global regulatory discussion,” Dr. Singh remarked.