The immunotherapy drug tarlatamab, a delta-like ligand 3 (DLL3) bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE), has been shown to be safe and efficacious in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients regardless of the presence of brain metastases, according to findings from an analysis of the phase II DeLLphi-301 study.

The findings were reported June 2 by Anne-Marie C. Dingemans, MD, PhD, of Erasmus MC Cancer Institute in Rotterdam, Netherlands, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting in Chicago.

In the DeLLphi-301 trial, an open-label, multicenter, multi-cohort study, investigators evaluated the antitumor activity and safety of tarlatamab, administered intravenously every 2 weeks at a dose of 10 mg or 100 mg, in patients with previously treated SCLC. Findings from the trial supported the recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of tarlatamab.

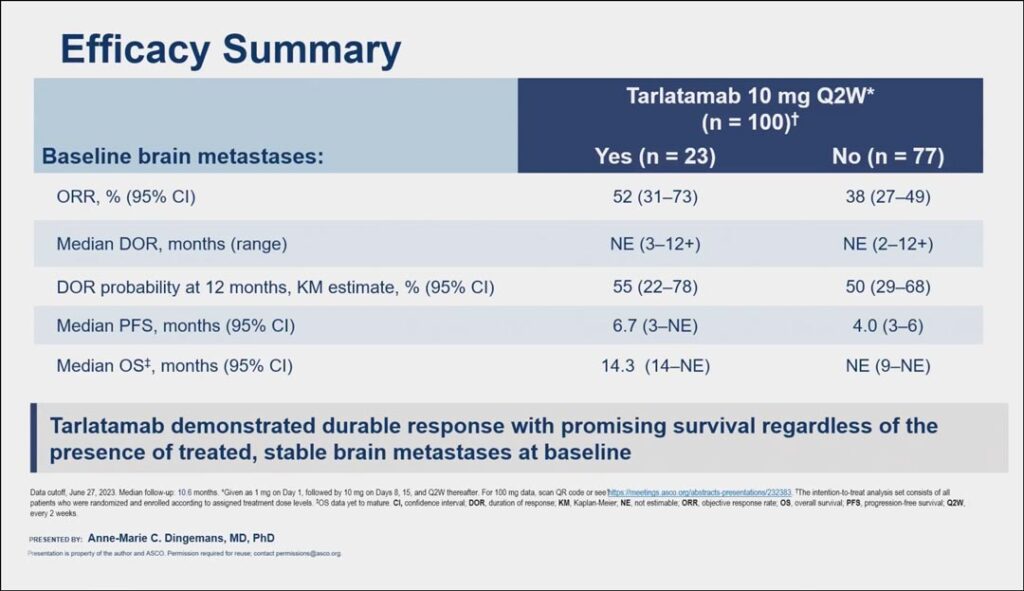

The major efficacy outcome measures of Dellphi-301 were overall response rate (ORR) per RECIST 1.1 and duration of response (DOR), as assessed by blinded independent central review. Dr. Dingemans said efficacy and safety results for patients who received the approved 10 mg dose was similar regardless of their baseline brain metastases status. The ORR rate for patients with baseline brain metastases was 52% compared to 38% for patients without baseline brain metastases and the median DOR probability at 12 months was 55% for patients with brain metastases and 50% for patients without. Additionally, the median PFS was 6.7 months and 4 months, respectively (see Fig. 1).

“Brain metastases are a frequent and a huge problem in patients with small cell lung cancer, so it is important to show this efficacy data for these patients,” she said. “Tarlatamab demonstrated durable response with promising survival regardless of the presence of treated, stable brain metastases at baseline.”

In an analysis of both cohorts of 186 patients who received tarlatamab in the DeLLphi-301 trial, Dr. Dingemans said 54 (29%) had treated and stable brain metastases at baseline, most of whom (91%) had received prior local radiotherapy, while 6% had undergone either surgery alone or both radiotherapy and surgery. The overall systemic objective response rate was 45.3% in patients with brain metastases and 32.6% in patients without brain metastases.

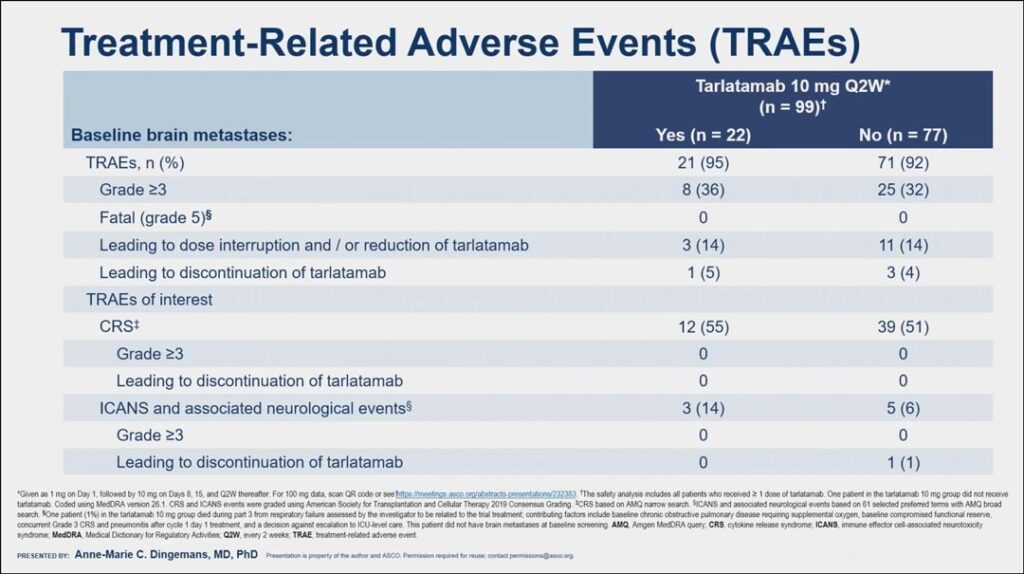

In their analysis, Dr. Dingemans indicated that the safety profile of tarlatamab in patients with brain metastases was manageable and consistent with the safety profile from the overall study. While tarlatamab has been associated with serious or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurologic toxicity, including immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), in the analysis, only eight patients receiving the approved 10 mg dose developed ICANS, and all cases were grade 1-2, though one case led to discontinuation of treatment (see Fig. 2).

“I was most interested in seeing whether there was difference in ICANS and associated neurological effects,” she said. “We know that patients with a high tumor burden and older age are at more risk for ICANS, but we see here that the patients with brain metastases at baseline did not have a higher risk of ICANS compared to patients without brain metastasis at baseline.”

A majority of patients (55% with brain metastases and 51% without brain metastases) developed CRS, but all cases were grade 1-2 and none led to discontinuation of treatment.

Additionally, Dr. Dingemans reported that central nervous system tumor shrinkage was observed in some patients treated with tarlatamab, but said more research is needed to flesh out this observation.

“This study has some limitations,” she said. “Intracranial results may be confounded by prior radiotherapy; the sample size of patients with baseline brain metastases of more than 10 mm was very small, and only patients with confirmed brain metastases at baseline had mandated brain MRI at follow-up. Tarlatamab is now FDA approved, and I think our data supports that it is safe to prescribe for these patients.”