Pan-Chyr Yang, MD, PhD

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide.1 Despite recent advances in precision therapy, which have greatly improved the treatment outcomes for lung cancer patients,2 the overall survival rates for those diagnosed with lung cancer remain poor. The 5-year survival rate is only about 21%.3 And while, tobacco smoking is the most important risk factor for lung cancer, the disease also occurs in people who have never smoked.3

The incidence of lung cancer among people who have never smoked is increasing globally.

It is estimated that 10% to 25% of lung cancer patients worldwide never smoked. Lung cancer in this subset of patients is more prevalent in East Asia, especially in women.1,5

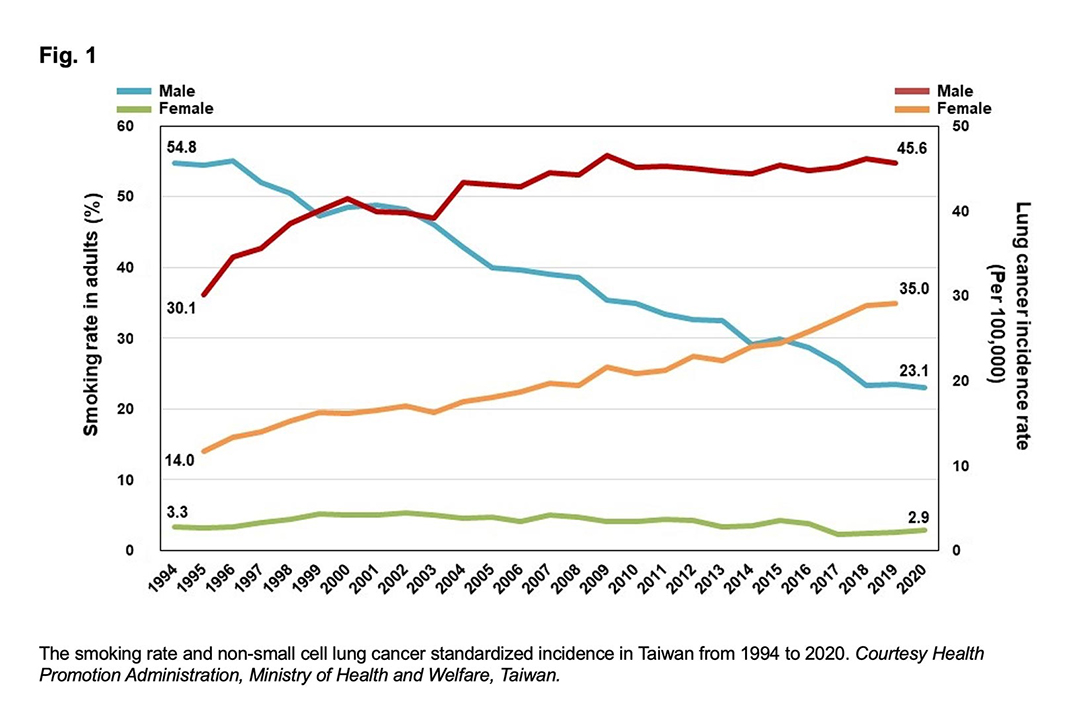

In Taiwan, we implemented a stop-smoking campaign in 1995, and the smoking rate in adult males has since decreased from 55% to 23%. The smoking rate in adult women remained stable at about 3%. However, the incidence of lung cancer—especially non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and adenocarcinoma subtype (Fig. 1)—keeps rising in both men and women.

More than half of lung cancer patients in Taiwan have never smoked, and among them, 58.7% present with stage 4 disease at initial diagnosis.6 Our recent proteogenomic study demonstrated that lung cancer in people who smoked and those that haven’t are two different diseases with distinct genetic profiles and pathogenic mechanisms. This highlighted the importance of genetic susceptibility and environmental carcinogen exposure.7 The risk prediction, strategy of prevention, management, and screening for early detection of lung cancer may need to be customized for people who have never smoked based on distinct epidemiology characteristics.

Screening Non-Smokers

Gee-Chen Chang, MD, PhD

Early detection of lung cancer is the most effective way to improve lung cancer survival. Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) lung cancer screening for high-risk smokers can effectively reduce lung cancer mortality.8,9 However, the effectiveness of LDCT for lung cancer screening in at-risk individuals who haven’t smoked is not clear.

Based on our previous studies on genetic epidemiology for lung cancer among these individuals, we conducted a nationwide lung cancer LDCT screening campaign for this population called TALENT (Taiwan Lung Cancer Screening for Never Smoker Trial). We aimed to develop an effective strategy to identify high-risk subjects for lung cancer screening among those who had never smoked.10

TALENT is a prospective, multicenter study sponsored by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) in Taiwan. Although participants had never smoked, they did to have one or more of the following risks:

- Family history of lung cancer within third-degree

- Passive smoking exposure

- Tuberculosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Cooking index score ≥ 110 (measured by number of times per week cooking included pan-frying, stir-frying, or deep-frying multiplied by number of years spent cooking)

- Cooking without ventilation

A total of 12,011 subjects were enrolled. Half the participants had a family history of lung cancer. The first-round screening results showed that lung cancer was diagnosed in 313 (2.6%) subjects. Of those, 255 (2.1%) were invasive lung cancers. All but one were adenocarcinoma and 96.5% were stage 0 or I, which means that the vast majority of the cases detected were in early stage and potentially curable.

We also found that family history of lung cancer may increase the risk of lung cancer. The prevalence of lung cancer was 3.3% and 2.0% in subjects with and without lung cancer family history, respectively. The TALENT study shows that LDCT screening of people who have never smoked but who have other risk factors may result in a beneficial stage-shift for this population.

Stage Shift to Improve Survival

Chao-Hua Chiu, MD

Identifying cases in earlier stages is a major byproduct of lung cancer screening that can help improve lung cancer survival. Based on the published lung cancer screening trials, such as National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) and NELSON, lung screening may shift lung cancer from an advanced incurable disease stage (stage 3-4) into an early curable disease (stage 0-1).

In the general population, only 24% of lung cancer cases are detected in stage 1. Comparatively, the NLST detected 63% of lung cancer patients in stage 1 disease and the NELSON trial 59%. This likely explains why these studies showed that screening could reduce lung cancer mortality by 20% to 24%. Our real-world evidence mirrors these findings.

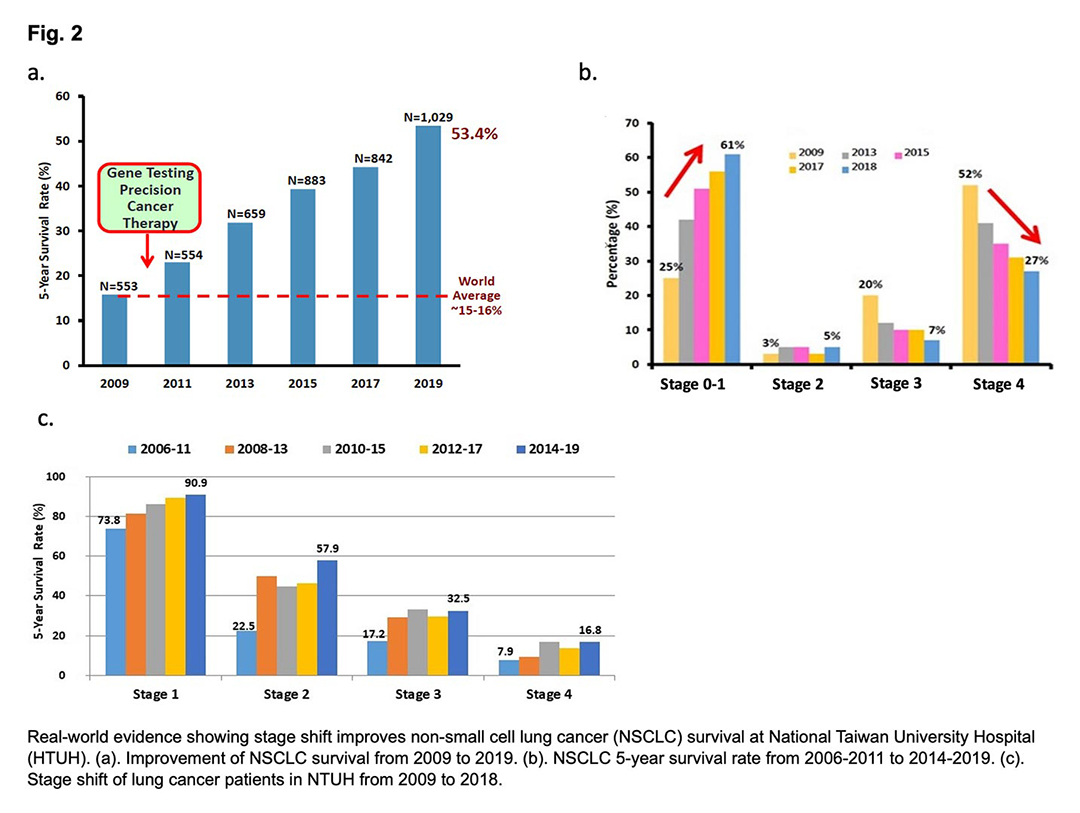

National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH) is one of the biggest Medical Centers in Taiwan. We see about 10% of lung cancer patients in Taiwan annually. Based on the cancer registry at NTUH, we started gene testing and precision therapy for lung cancer in 2010. At that time the NSCLC 5-year survival rate was only 16%.

Currently, the 5-year survival rate has dramatically improved to 53% (Fig. 2a). We nearly doubled the 5-year survival of stage 4 disease patients from 8% to 17% during the past decades because of the implementation of precision cancer treatment (Fig. 2b). However, we have found the main reason for the improvement in 5-year survival rates is likely attributable to stage shift. The incidence of stage 1 disease increased from 25% in 2009 to 61% in 2018 and stage 4 disease decreased from 52% to 27% (Fig. 2c). This real-world evidence suggests that screening-mediated stage shift may be the best strategy to improve lung cancer survival.

Policy and Public Awareness

Since lung cancer has the highest disease burden in terms of cancer mortality and health resource expenses, our national cancer control program has set a goal to tackle this dreadful disease in Taiwan by aiming to reduce the lung cancer death rate an additional 25% by 2025. To achieve this goal and increase public awareness of the importance of lung cancer screening, we published a handbook for medical professionals and for the general population.

The first version of the consensus handbook for LDCT lung cancer screening was created by a joint task force from three medical societies—Taiwan Lung Cancer Society, Taiwan Society of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, and Taiwan Radiological Society—in 2015. In 2020, a fourth society—Taiwan Society of Thoracic Surgeons—joined to endorse a second version. The handbook comprehensively covers the newest evidence of LDCT lung cancer screening, other screening tools, benefits and harms, cost-effectiveness of LDCT screening, and recommendations for managing pulmonary nodules detected by LDCT. (Fig. 3a)

Chong-Jen Yu, MD, PhD

The LDCT program was adapted as an optional item in the health exam of many medical institutes after the publication of the NLST study in 2011. Because of media exposure, many large organizations in Taiwan continuously advocate for the incorporation of LDCT into the national cancer screening program. Legislators have also called public hearings on this issue. In response to this appeal, several local governments now support LDCT screening for people with certain occupations, such as police officers, firefighters, farmers, and fishermen.

The Health Promotion Agency (HPA) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) provides detailed information (text, videoclips, and handbook, Fig. 3b) regarding LDCT to citizens on its website and has prepared to commence a LDCT lung cancer screening program for heavy smokers and for non-smokers with a family history of lung cancer.

Screening Consensus in East Asia

Because of the regional differences of lung cancer epidemiology in East Asia,7,11,12 we initiated a steering committee in 2021, aiming to develop a consensus for lung cancer screening in East Asia. The committee consists of 19 advisors from 11 Asian countries and the senior advisor of scientific affairs for IASLC, Murry Wynes, PhD. The objectives are to evaluate current lung cancer screening and early diagnosis practices in various countries in East Asia, discuss the risk factors in Asian populations to systematically guide lung cancer screening efforts, prioritize populations for LDCT screening, and to consider an integrated approach to expand lung health screening. We believe the support of innovative modalities will lead to lung cancer screening policy changes in individual countries.

The committee intends to develop a consensus to highlight the importance of lung cancer screening, create a guide to identify the high-risk populations warranting screening, and address the current barriers to implementation of screening programs and ways to overcome them for earlier detection of lung cancer in East Asia.

References

- 1. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 29 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study [published correction appears in JAMA Oncol. 2020 Mar 1;6(3):444] [published correction appears in JAMA Oncol. 2020 May 1;6(5):789] [published correction appears in JAMA Oncol. 2021 Mar 1;7(3):466]. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1749-1768. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2996

- 2. Yang CY, Yang JC,Yang PC. Precision management of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2020 Jan 27;71:117-136.

- 3. Lung Cancer – Statistics. Cancer.net. 2021

- 4. Toh CK, Gao F, Lim WT, et al. Never-smokers with lung cancer: epidemiologic evidence of a distinct disease entity. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2245-51.

- 5. Zhou F and Zhou C, Lung cancer in never smokers-the East Asian experience. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018;7(4):450-463.

- 6. Lo YL, Hsiao CF, Chang GC, Tsai YH, Huang MS, Su WC, Chen YM, Hsin CW, Chang CH, Yang PC, Chen CJ, Hsiung CA. Risk factors for primary lung cancer among never smokers by gender in a matched case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2013 Mar;24(3):567-76.

- 7. Tseng CH, Tsuang BJ, Chiang CJ, et al. The Relationship Between Air Pollution and Lung Cancer in Nonsmokers in Taiwan. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:784-92.

- 8. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409.

- 9. de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503-513

- 10. Yang P. National Lung Cancer Screening Program in Taiwan: The TALENT Study. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:S58.

- 11. Shi Y, Au JS, Thongprasert S, et al. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology (PIONEER). J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(2):154-62.

- 12. Huang J, Deng Y, Tin MS, et al. NCD Global Health Research Group, Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU). Distribution, risk factors, and temporal trends for lung cancer incidence and mortality: a global analysis. Chest. 2022 Jan 10:S0012-3692(22)00017-4.