A wide range of nations at various stages of economic and health-system development fall under the umbrella of low- and middle-income countries (LIMC). As Lucía Viola, MD, of the Fundación Neumológica Colombiana in Bogota, Colombia, explained during a talk in which she addressed lung cancer screening implementation in these countries, LMIC “comprises regions where communicable diseases are still pressing public health problems and countries that currently face extremely fragile situations with uninterrupted armed conflict, as in my country, and nonfunctioning health care systems.”

With these challenges to contend with, lung cancer screening does not rank high on the list of priorities for many LIMC. And yet, in such countries, “there is a direct relationship between advanced disease and higher expenses, suggesting that noncurative treatment costs may be higher than the cost of implementing screening programs,” Dr. Viola explained.

In her talk, Dr. Viola focused on several shortcomings and strategies that require attention in order to establish organized population-based lung cancer screening programs in LMIC.

Research on Lung Cancer Risk Factors

Smoking ranks as the leading risk factor for lung cancer incidence in LMIC. “Over 80% of the 1.3 billion smokers worldwide reside in LMIC, accounting for more than 70% of all global smoking-related deaths. The increasing smoking prevalence that is associated with changes in tobacco habits and expanding tobacco markets, combined with the often-large populations of LMIC, is generating profound public health challenges with substantial consequences expected in the decades to follow,” Dr. Viola stated.

This underscores the importance of smoking-cessation initiatives, which Dr. Viola believes should be integrated into lung cancer screening programs. Indeed, modeling research supports the benefit of smoking cessation when rolled out in tandem with lung cancer screening, as illustrated by a reduced number of deaths from lung cancer, years of life gained, and a reduced probability of death from other causes.1

Dr. Viola also argued that combining smoking-cessation efforts with screening can improve the cost-effectiveness of lung cancer screening programs.

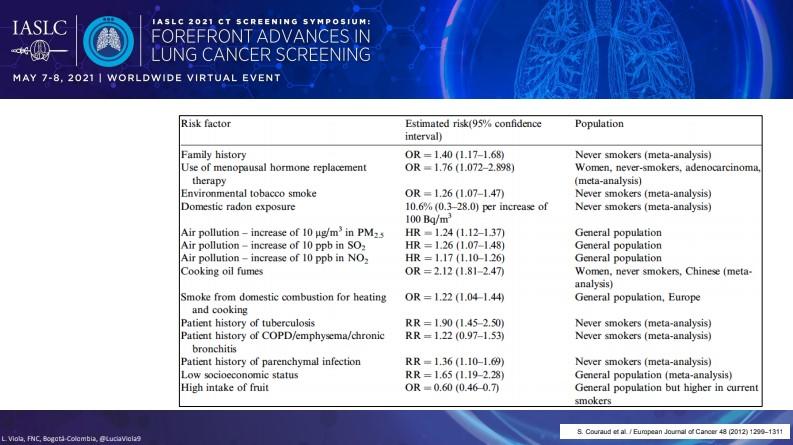

In addition to risk-reduction efforts focused on smoking, Dr. Viola stressed that other factors that contribute to lung cancer risk in LMIC need greater attention given that never-smokers comprise an increasingly larger share of all lung cancer cases as time goes on. These other risk factors include domestic radon exposure, air pollution, and smoke from oil used for heating and cooking, among others (Figure).2

Research on LDCT Screening in LMIC and Adapted Guidelines

In terms of other data gaps, “the evidence for the efficacy of low-dose CT screening in LMIC is scarce, so we need more research on these topics for the future,” Dr. Viola remarked.

Some low-dose CT (LDCT) screening studies have been conducted in China, India, and Russia, but most are still ongoing with little data available as of yet.3

However, such research is of great importance in LMIC given the high prevalence of granulomatous disease, tuberculosis, and other pulmonary diseases that might complicate the screening process.

Results from the First Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT1) showed that applying the US National Lung Cancer Screening Trial screening criteria to the Brazilian population, which features a high incidence of granulomatous disease, resulted in a larger number of positive scans based on the presence of nodules compared with previous lung cancer screening studies (39.5% vs 26%).4

Despite this, the rate of surgical biopsy (3.1%) and the incidence of lung cancer (1.3%) was similar to prior studies, suggesting that the high prevalence of granulomatous disease in Brazil did not increase the number of false-positive results.

Dr. Viola argued that it would be helpful for regional medical societies to develop guidelines that specifically address issues like this to help direct LMIC regarding the implementation of appropriate lung cancer screening criteria in accord with the endemic diseases common in various areas.

Access to Screening

Dr. Viola detailed several obstacles pertaining to screening access in LMIC, along with potential solutions. “Lack of transportation, long travel distances, and poor road conditions can make healthcare practically inaccessible, especially in rural areas,” she remarked. “These could be solved with mobile CT scanners or provision of complementary transportation to the eligible population.”

Educating primary care physicians (PCPs) about screening guidelines may also be an effective strategy for improving lung cancer screening in LMIC. As part of this education, PCPs need to be armed with knowledge about how to discuss the benefits and potential harms of screening with individuals. Optimizing “an affordable provider education program should be a priority in early implementation phases,” Dr. Viola said.

Treatment Continuity

Before a population-based screening program is implemented, Dr. Viola stressed that it is important to ensure that the proper infrastructure to support the program is already in place. Factors to take into account include an increased demand for CT scans and biopsy procedures related to the study of lung nodules, as well as a sufficient number of radiologists well-versed in using Lung-RADS and volumetric-based measurement guidelines. Yet another important resource includes multidisciplinary teams consisting of surgeons, radiologists, and pulmonologists with experience in bronchoscopy to guarantee treatment continuity once a lung cancer diagnosis is made.

- 1. Cao P, Jeon J, Levy DT, et al. Potential impact of cessation interventions at the point of lung cancer screening on lung cancer and overall mortality in the United States. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(7):1160-1169.

- 2. Couraud S, Zalcman G, Milleron B, Morin F, Souquet PJ. Lung cancer in never smokers–a review. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(9):1299-1311.

- 3. Edelman SE, Guerra RB, Edelman SM. et al. The challenges of implementing low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:1140-1152.

- 4. dos Santos RS, Franceschini JP, Chate RC, et al. Do current lung cancer screening guidelines apply for populations with high prevalence of granulomatous disease? Results from the First Brazilian Lung Cancer Screening Trial (BRELT1). Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(2):481-486.