Manan P. Shah, MD

Cancer leads to higher per-person costs than any other disease, and unplanned hospital care is one of the biggest drivers of expenses in cancer care.1 Lung cancer contributes to the largest share of unplanned oncologic care, because of both its prevalence and its high rate of hospital care utilization compared to other cancer types.2 When patients with lung cancer present to the emergency department (ED), the root cause is often presumed to be either the cancer or its therapy, but there is a lack of data on this topic.

In our retrospective study published in JCO Oncology Practice,3 we investigated the proportion of ED visits by patients with NSCLC that were attributable to the cancer versus its medical therapies: TKI therapy, immune-checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy, and cytotoxic chemotherapy. We also analyzed each ED visit to: (1) understand the key drivers of unplanned hospital care, and (2) identify strategies to prevent the need for such visits.3

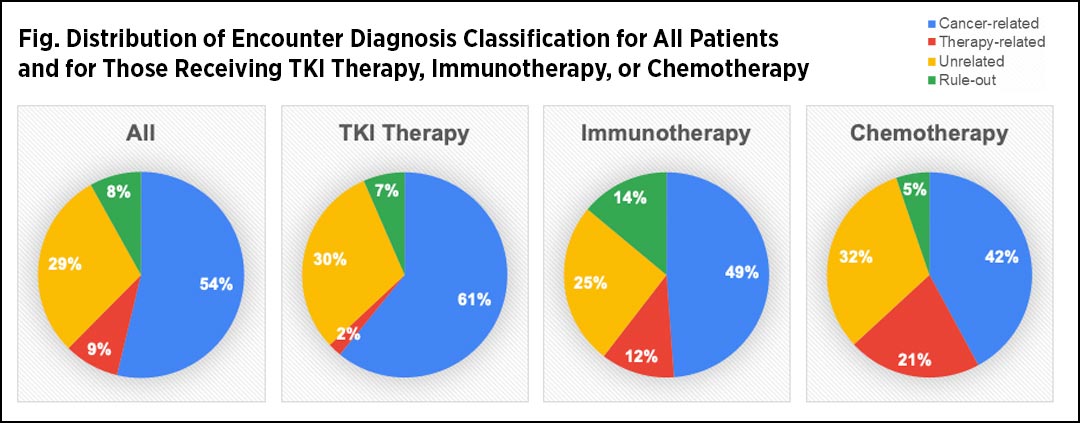

Using the STAnford medicine Research data Repository (STARR), we identified 173 ED visits in 2018 made by 97 patients with NSCLC who had received TKI therapy, immunotherapy, or chemotherapy within the 3 months before their ED visit. Through retrospective analysis, we classified each ED visit into four categories: cancer related (e.g., dyspnea due to malignant pleural effusion), therapy related (e.g., hypoxia due to treatment-induced pneumonitis), unrelated to cancer or therapy (e.g., acute coronary syndrome), and “rule-out” (e.g., urgent imaging to rule out pulmonary embolism).

Joel W. Neal, MD, PhD

We also labeled ED visits as potentially “preventable” if we concluded that the encounter could have been feasibly addressed and adequately managed in the outpatient setting. To be classified as preventable, the encounter had to meet each of these conditions: (1) the patient’s chief complaint began at least 2 or more days prior to presentation, (2) the diagnostics and/or therapeutics could have been provided in an ambulatory setting (e.g., clinic, urgent care), and (3) the patient was discharged directly from the ED. Of these preventable encounters, those that were made during our business hours were additionally labeled “unnecessary,” as those visits could have been conducted by our clinic or infusion room–based sick-call teams.

Therapy-related encounters accounted for 9% of all ED visits, a smaller portion than we had expected prior to conducting this analysis. As we had expected, there was a significantly smaller portion of therapy-related encounters in the TKI-therapy group (2%) than in the immunotherapy group (12%), which in turn had a significantly smaller portion than the chemotherapy group (21%; expanded Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001). In all groups, the leading cause of ED encounters was the underlying cancer itself, and a large portion of cases were deemed to be not directly related to either cancer or therapy (Fig.). This finding was reassuring, as providers are consistently forced to weigh the risks and benefits of prescribing such therapies and to consider underlying comorbidities.

To our surprise, we found that many of the ED visits were during business hours (52%), were for complaints that began 2 or more days prior to presentation (53%), led to diagnostics and/or therapeutics that could have been administered in an outpatient setting (48%), and did not lead to admission (55%). Consequently, 24% of the ED visits met each of those criteria and were classified as preventable, as they could have been addressed in an ambulatory setting. About half of the preventable visits (more than 10% of all visits) occurred during business hours and were also classified as unnecessary. These unnecessary visits were a result of patients and providers using the ED for urgent issues when an ambulatory avenue was not only more appropriate but also readily available.

These findings suggest that a significant portion of unplanned hospital care for patients with lung cancer might be managed with early intervention, extension of ambulatory care services, and patient and provider education regarding the various available avenues of urgent care. Our institution has sought to reduce such unplanned hospital care by expanding procedure clinics (e.g., thoracentesis clinic) and increasing the staffing of our infusion room–based sick-call services. We are implementing a triage system—when providers get calls or see patients in clinic who need urgent medical care, they can simply page a designated provider, who will then assess the patient and direct them to the appropriate avenue of care (e.g., clinic or pharmacy, urgent care, ED).

Future changes to our system include extending the hours of our urgent-care sick-call system and developing remote digital-monitoring platforms to identify patients with worsening symptoms, allowing for earlier ambulatory intervention. Data from studies such as ours will be useful in assessing the relative impact of these strategies in preventing unplanned care, which we hope will help improve quality of life and decrease health care costs for patients with cancer.

References:

- 1. Brooks GA, Li L, Uno H, et al. Acute Hospital Care Is the Chief Driver Of Regional Spending Variation In Medicare Patients With Advanced Cancer. Health Affairs. 2014;33(10):1793-1800.

- 2. Whitney RL, Bell JF, Tancredi DJ, et al. Unplanned Hospitalization Among Individuals With Cancer in the Year After Diagnosis. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(1):e2-e29.

- 3. Shah MP, Neal JW. Relative Impact of Anticancer Therapy on Unplanned Hospital Care in Patients With Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Oncology Practice. 2021;17(8):e1131-e1138.