Ticiana A. Leal, MD

Squamous NSCLC (sqNSCLC) is a challenging disease to manage because most patients present with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease1,2. sqNSCLC is a genomically complex disease with a high mutation rate, and alterations in DNA damage pathways—including smoking-associated damage3-5.

The current standard of care for treatment of patients with advanced sqNSCLC includes immunotherapy as monotherapy or immunotherapy combinations with chemotherapy6-7. However, only a small subset of patients achieves durable benefit with these strategies. Although advances with targeted therapy have improved patient outcomes in nonsquamous NSCLC, the same successes have not been realized in sqNSCLC.

There has been great interest beyond breast cancer in investigating the addition of poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) to the treatment armamentarium for patients with advanced solid tumors harboring DNA damage alterations, including lung cancer8-9. Germline BRCA1/2 mutations are well-established predictive biomarkers of PARPi sensitivity,10-12 and predict sensitivity to PARPi monotherapy in metastatic breast13,14 and ovarian15-17 cancers. PARPi is also used as maintenance therapy in metastatic ovarian18,19 and pancreatic20 cancers. Multiple trials have identified additional somatic or germline alterations in DNA damage repair (DDR) pathway genes associated with PARPi sensitivity21 including germline PALB2 mutations and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations in metastatic breast cancer22 and germline or somatic BRCA1/2 and ATM alterations in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer23,24.

Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD

In a randomized phase II trial of veliparib or placebo in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel (C and P) for advanced NSCLC (including squamous and adenocarcinoma), outcomes were favorable in the veliparib arm for patients with squamous histology (HR of 0.54 and 0.73 for PFS and OS, respectively), suggesting the addition of veliparib could benefit these patients25. Clinical benefit was also observed in those patients who smoked at the time of the study (defined as having smoked within 12 months of study entry and had more than 100 smoking events/cigarettes, in their lifetime), with improved PFS and OS for patients who received veliparib versus placebo (HR of 0.38 and 0.43 for PFS and OS, respectively)26.

The signal of efficacy in the phase II study led to a global randomized study in the phase III setting investigating the combination of veliparib (120 mg twice a day) or placebo for 7 days with C and P for up to six cycles in patients with advanced sqNSCLC. Of note, enrollment preceded the approval of immunotherapy as first-line treatments for sqNSCLC.

The primary endpoint of the study was OS for patients who were defined as current smokers. Secondary end points included OS in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (all randomly assigned patients), and PFS and overall response rate (ORR) in current smokers and the ITT population.

In this study, 970 patients were randomly assigned to C and P plus veliparib (n = 486) or placebo (n = 484). Most patients were male (82%), with a median age of 64 years. Current smokers accounted for 57% of the study population. There were no clinically meaningful differences in baseline demographics or disease characteristics between treatment arms.

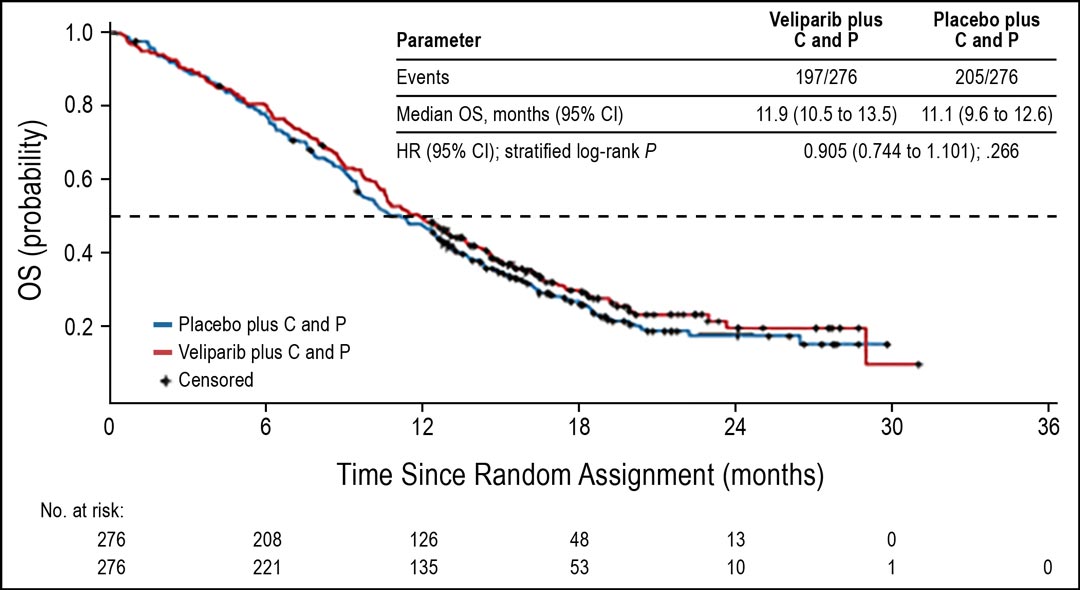

The phase III study did not meet its primary endpoint of improvement in OS for patients with advanced sqNSCLC who were identified as current smokers; with median OS of 11.9 in the veliparib combination arm compared with 11.1 months in the placebo arm (HR = 0.905; 95% CI: 0.744–1.01; p = 0.266; Fig 1).

Of note, in the phase II study median PFS (6.5 vs. 4.1 months, HR = 0.54; 95% CI: 0.26–1.12, p = 0.098) and OS (10.3 vs. 8.4 months, HR = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.43–1.24, p = 0.24) were favorable with veliparib treatment for patients with the squamous histologic subtype. Disappointingly, this did not translate to benefit in the phase III study.

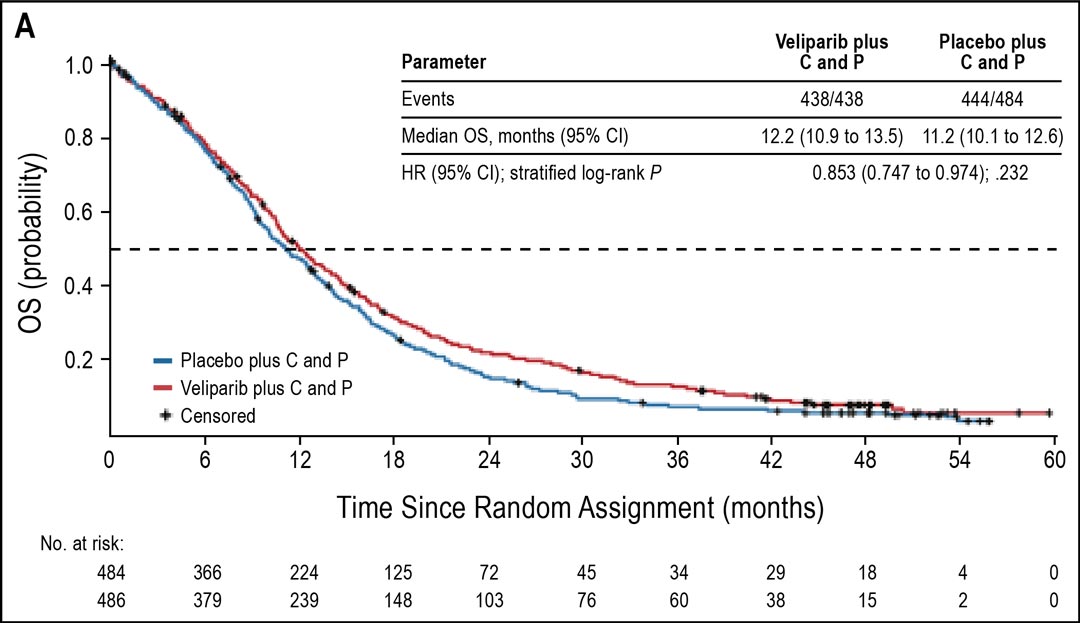

Figure 1. OS in current smokers. Abbreviations: C, carboplatin; P, paclitaxel Subsequently, OS in the ITT population was analyzed in a descriptive manner. OS in the ITT population favored veliparib over placebo, with median OS of 12.2 versus 11.2 months (HR = 0.853; 95% CI: 0.747–0.974; nominal P = .032; Fig 2). Median PFS in the ITT population was similar for both arms (5.6 months for both arms; HR = 0.897; 95% CI: 0.779–1.032; nominal P = .107). The ORR was also similar in both arms (37%).

Fig 2. OS in all ITT patients

In this study, patients provided tissue for biomarker analysis. A specific informatic LP52 classifier was developed using independently derived RNA-seq data from a training cohort of 120 tumors representing a diverse set of NSCLC subtypes. LP52 has two subtypes (adenocarcinoma and nonadenocarcinoma), and each gene was normalized within a cohort of squamous histology samples. LP52 positivity was assigned to tumors with nonadenocarcinoma characteristics27. The authors hypothesized that patients with sqNSCLC and molecular characteristics of adenocarcinoma might derive less clinical benefit from veliparib than patients with nonadenocarcinoma molecular characteristics.

In patients with biomarker-evaluable tumor samples (n = 360), OS favored veliparib in the LP52-positive population (median 14.0 vs. 9.6 months; HR = 0.66; 95% CI: 0.49–0.89) but favored placebo in the LP52-negative population (median 11.0 vs. 14.4. months; HR = 1.33; 95% CI: 0.95–1.86).

No new safety signals were observed. Grade 3 or 4 adverse events (AEs) attributed to the study drug were experienced by 20% of patients in both treatment arms, the most frequent being neutropenia (9% in both arms). Most neutropenia events were nonserious, and infections were infrequent in both arms. AE-related deaths occurred in 38 (7.8%) patients in the veliparib arm and 44 (9.1%) in the placebo arm, and most were considered unrelated to study drugs.

In summary, the hypothesis generated from the phase II study suggesting that efficacy of veliparib in current smokers could reflect the effect of this drug on DNA repair pathways and in reducing genomic instability was not confirmed in the phase III study. A potential biomarker in the form of LP52 signature may identify a subset of patients who benefit from addition of veliparib to chemotherapy. It is unlikely that chemotherapy plus PARPi strategy will be pursued further in NSCLC because of the integration of immune checkpoint inhibitors in this setting.

However, the combination of PARPi plus immune checkpoint inhibition is already in advanced stages of evaluation. Studies to watch include A Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) With or Without Maintenance Olaparib in First-line Metastatic Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (ID: NCT03976362) and Study of Pembrolizumab With Maintenance Olaparib or Maintenance Pemetrexed in First-Line Metastatic Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (ID: NCT03976323).

References

- 1. Socinski M, Obasaju C, Gandara D, et al. Current and Emergent Therapy Options for Advanced Squamous Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(2):165-183.

- 2. Socinski M, Obasaju C, Gandara D, et al. Clinicopathologic Features of Advanced Squamous NSCLC, in Obasaju C (ed). J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(9):1411-1422.

- 3.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489(7417):519-525.

- 4.Deng L, Kimmel M, Foy M, Spitz M, Wei Q, Gorlova O. Estimation of the effects of smoking and DNA repair capacity on coefficients of a carcinogenesis model for lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(9):2152-2158.

- 5.Paz-Elizur T, Krupsky M, Blumenstein S, Elinger D, Schechtman E, Livneh Z. DNA repair activity for oxidative damage and risk of lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(17):1312-1319.

- 6. Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040-2051.

- 7. Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, et al. NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2022 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. Accessed January 14, 2022.

- 8. Pilié PG, Gay CM, Byers LA, O’Connor MJ, Yap TA. PARP inhibitors: Extending Benefit Beyond BRCA-mutant cancers. Clin Cancer Research. 2019;25(13):3759-3771.

- 9. Jiang Y, Dai H, Li Y, et al. PARP inhibitors synergize with gemcitabine by potentiating DNA damage in non-small cell lung cancer. 2019;144(5):1092-1103.

- 10. Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434(7035):913-917.

- 11. Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434(7035):917-921.

- 12. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):123-134.

- 13. Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(8):753-763.

- 14. Robson M, Goessl C, Domchek S. Olaparib for Metastatic Germline BRCA-Mutated Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1792-1793.

- 15. Matulonis UA, Penson RT, Domchek SM, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced relapsed ovarian cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation: a multistudy analysis of response rates and safety. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(6):1013-1019.

- 16. Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(3):244-250.

- 17. Oza AM, Tinker AV, Oaknin A, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with high-grade ovarian carcinoma and a germline or somatic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: Integrated analysis of data from Study 10 and ARIEL2. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147(2):267-275.

- 18. Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2154-2164.

- 19. Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1274-1284.

- 20. Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):317-327.

- 21. Lord CJ, Ashworth A. BRCAness revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(2):110-120.

- 22. Tung NM, Robson ME, Ventz S, et al. TBCRC 048: Phase II Study of Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer and Mutations in Homologous Recombination-Related Genes. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(36):4274-4282.

- 23. de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2091-2102.

- 24. Hussain M, Mateo J, Fizazi K, et al. Survival with Olaparib in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2345-2357.

- 25. Ramalingam S, Blais N, Mazieres J, et al. Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase II Study of Veliparib in Combination with Carboplatin and Paclitaxel for Advanced/Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(8):1937-1944.

- 26. Reck M, Blais N, Juhasz E, et al. Smoking History Predicts Sensitivity to PARP Inhibitor Veliparib in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thoracic Oncol. 2017;12(7):1098-1108.

- 27. Faruki H, Mayhew G, Fan C, et al. Validation of the Lung Subtyping Panel in Multiple Fresh-Frozen and Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Lung Tumor Gene Expression Data Sets. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(6):536-542.