Sreeram Ramagopalan, PhD

Historically, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been the ideal source of evidence to support regulatory and reimbursement decision-making for new health technologies. However, the development of therapies that target relatively rare oncogene defined sub-groups of lung cancer patients and our desire to provide patients with earlier access to effective agents, have resulted in an increasing number of new medicines being launched with single-arm clinical trial data.

To provide comparative effectiveness and safety data for regulators and payers, investigators have increasingly looked to compare such single-arm clinical trial data to control data from external sources, such as historic trials or real-world data (RWD) sources. However, concern about the potential for results from these non-randomised comparisons to be biased limits the extent to which such analyses can support decision-making.

For a study in JAMA Network Open1 in 2021, our team—led by Samantha Wilkinson, PhD—revisited a historic example to test if the use of additional real-world data and sensitivity analysis methods would support the findings of the original analysis.

The example explored in the study was that of alectinib, which obtained regulatory approval for the treatment of crizotinib-refractory ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in several countries based on two distinct phase 2, single-arm trials.

However, the evidence base for alectinib was not enough to convince payers in some countries of the additional benefit it would provide compared to the standard of care in this indication. In most of these markets, the standard-of-care was ceritinib, a second generation ALK inhibitor. The key evidence supporting the benefit of alectinib compared to ceritinib was a non-randomised comparison of data from the phase 2 trials of alectinib against real-world data on ceritinib from Flatiron Health, a large US electronic health record database.2

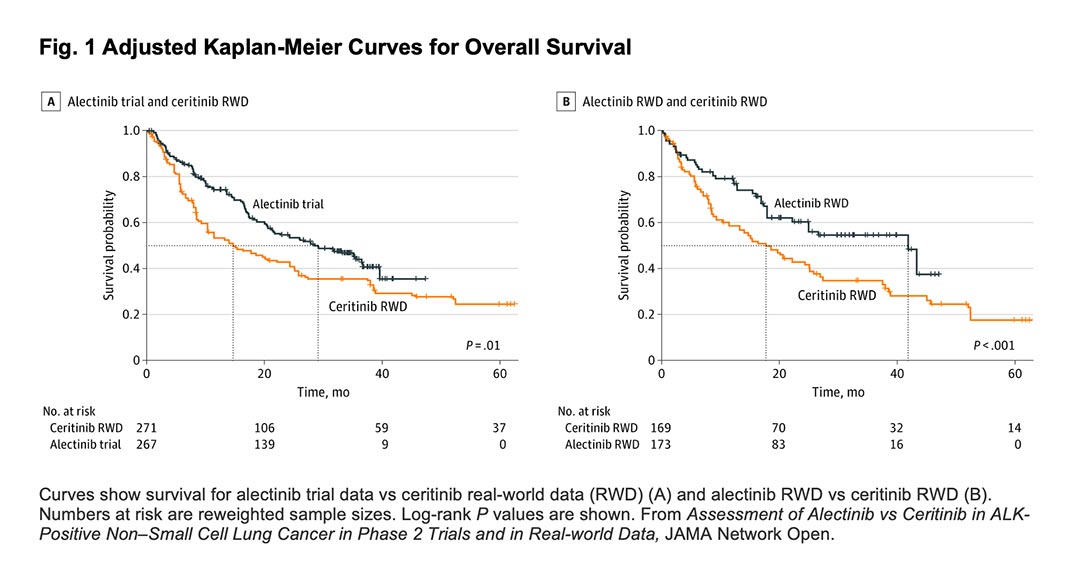

This analysis reported relatively large benefits for alectinib with hazard ratios for all-cause death of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.48-0.88) and 0.58 (95% CI, 0.44-0.76), depending on the analytic method used. This translated to an approximate 40% reduction in death rates.

Despite the potential benefit observed, payers were concerned about the analysis.

Concerns included the limited follow-up of patients, the differing selection criteria governing entry to the trial compared to real-world data, and the potential for bias caused by partially or completely missing data.

In the study, our team repeated the original non-randomised comparison using updated data from the Flatiron Health database. We demonstrated that with additional patients and a longer duration of follow-up, results similar to that of the original analysis were obtained. This finding suggests that the relative survival benefits demonstrated for alectinib in the original analysis were not an artifact of the limited follow-up data available.

Since real-world data on alectinib were now available, the authors also carried out a comparison of real-world data on both alectinib and ceritinib from Flatiron Health, thereby addressing the criticism of the differing selection criteria of the trial compared to the real-world data.

Interestingly, this analysis produced relatively similar results to the comparison between the clinical trial data and the real-world data, suggesting that the hypothesized selection criteria were unlikely to have explained the original benefit of alectinib observed.

Finally, we applied a set of sensitivity analyses that explored how large a problem— such as confounding and missing data—would have to be to fully explain the results observed. These analyses demonstrated that these issues would have to have been of an unrealistically large magnitude to explain the results observed.

For example, an unmeasured factor that was as prognostic as Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status would have to have been twice as common in one treatment group compared to the other to explain the results. Similarly, the true values of those patients with missing data on ECOG performance status would have to have been heavily skewed across treatment groups to explain the results obtained.

These findings build on those of other studies that have demonstrated that with appropriate study design and analysis, external control arms derived from high-quality, real-world data sources can reproduce the findings of RCTs.

Importantly, they also suggest that while the findings of non-randomized comparisons based on real-world data may be associated with greater uncertainty, regulators and payers should remain open to the possibility of using quantitative methods to support decision-making in the face of such uncertainty. A failure to do so may delay or restrict patient access to valuable treatments such as alectinib.

References

- 1. Wilkinson S, Gupta A, Scheuer N, et al. Assessment of Alectinib vs Ceritinib in ALK-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Phase 2 Trials and in Real-world Data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2126306. Published 2021 Oct 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.26306

- 2. Davies J, Martinec M, Delmar P, et al. Comparative effectiveness from a single-arm trial and real-world data: alectinib versus ceritinib. J Comp Eff Res 2018. Sep;7(9):855-865